You are here

Enlarging the visual orb

By Sally Bland - Sep 24,2017 - Last updated at Sep 24,2017

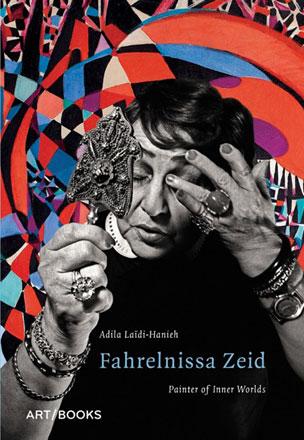

Fahrelnissa Zeid: Painter of Inner Worlds

Adila Laidi-Hanieh

UK: Art Books Publishing, 2017

Pp. 288

Two events this year attest to the continuing attraction of Fahrelnissa’s monumental artistic production, 26 years after her death. One is the June opening of a major exhibition of her works at the Tate Modern in London, which will later travel to Berlin and Beirut.

The other is the publication of this book in which cultural researcher Adila Laidi-Hanieh, once Fahrelnissa’s student, intertwines biography and art history to present a comprehensive picture of her life and work, which almost literally spanned the 20th century.

This is a tall order when writing about such a prolific person whose life was so full of events. Taking her cue from Fahrelnissa, who refused to compartmentalise her life into personal and artistic domains, the author succeeds remarkably in revealing the dynamics linking the person with her creativity.

Though Fahrelnissa received much recognition in her lifetime, critics often assigned her art to an exotic Orientalist box, attributing her aesthetic choices to her Middle East origins. In contrast, Laidi-Hanieh argues convincingly for releasing her from this box, because “it distracts from the individuality and contemporaneity of Fahrelnissa’s practice”. (p. 166)

Born into an illustrious Ottoman family and married into a royal one, the Hashemites, Fahrelnissa was proud of both, and never denied her Turkish origins or Arab affiliations. Still, the author’s meticulous research, detailed analysis of scores of paintings and of Fahrelnissa’s changing styles and associations with other artists in Turkey, France, Germany and England — all point to European influences, from the Old Masters to Kandinsky, as being more important to her development.

Laidi-Hanieh pays ultimate respect to Fahrelnissa by taking her at her word about her inspirations and motives, quoting extensively from her diaries and other writings which point to her more expansive, universalist, even cosmic affiliations, as well as to her spiritual and intellectual depth. As she wrote in a 1949 diary entry: “Why must we always see with the eyes of this world, why not see farther and enlarge the visual orb and reach even the divine, in a circle traversed by cosmic waves”. (p. 124)

Even her characteristically anti-naturalistic portraits, while departing from her usual focus on colour, light and motion, were grounded in spirituality, as she strove to capture the subject’s inner life. According to the author, “Fahrelnissa’s sublime was not simply an artistic choice; it was a projection of her own exaltation during the painting process”. (p. 190)

The book examines Fahrelnissa’s stylistic trajectory from figurative to Expressionist to abstract which led to her huge canvases of kaleidoscopic whirls of boldly vibrating colors and shapes, marked off by thick black lines. This was not an entirely linear process, and Fahrelnissa gave various explanations for her move to abstraction, but Laidi-Hanieh connects it to her vision. “By 1949… she had embraced a conception of abstraction as a process of artistic maturity, of communion with the absolute, as a voyage into the infinite, a purification, and a liberation from the limited world of objects and figuration.” (p. 122)

Laidi-Hanieh’s elegant prose brings to life the rich cultural environment in which Fahrelnissa lived and which she created around her, whether in Istanbul, Paris, London or Amman. While in many ways Fahrelnissa was privileged, the author poignantly conveys the extent to which her life was a struggle to be who she was and to do what she wanted, a struggle to overcome the many personal losses and bouts of depression she faced, and a struggle with herself in art where she “engaged in quasi-physical combat with her canvases”. (p. 131)

Reading this book, one understands the enigmatic line in Fahrelnissa’s poem: “I ran to the inferno and the inferno engulfed me and this is why I am happy”. (p. 222)

Laidi-Hanieh’s in-depth research and obvious knowledge of the art scene in Turkey and Europe in Fahrelnissa’s time enable her to present select incidents which attest to the artist’s determined struggle. It all began with convincing her family to send her to art school in Istanbul at a time when girls stayed home waiting to marry; it continued with her ability to embrace critique at the free academy in Montparnasse in 1928, spurring her development into a significant contributor to the modern art movement.

The greatest struggle was adapting after the 1958 coup in Iraq in which several of her beloved husband Prince Zeid’s family members were killed, and he lost his position as Iraq’s ambassador to Britain. Despite their devastation, Fahrelnissa was soon engaged in inventing new art forms.

The book’s excellent text is enriched by truly stunning images of Fahrelnissa’s paintings, as well as sketches and photos, and a comprehensive chronology of her life events and multiple exhibitions.

Many in Jordan have reason to be thankful that Fahrelnissa chose to spend her last years in Amman, to be near her son, Prince Raad, for she practically introduced abstract art to the country and devoted a lot of her time to giving free art lessons. Much of Laidi-Hanieh’s research was carried out here, thanks to the help of Prince Raad and Princess Majda, Suha Shoman of Darat Al Funun, and others.

There will be a book signing and discussion with the author at Darat Al Funun on September 26 at 6:30pm.

Related Articles

Fahrelnissa and I: A MemoirJanset Berkok ShamiIstanbul: Cinius Publishing House, 2016Pp.

AMMAN — In her latest book, author Janset Berkok Shami reminisces on 16 years of friendship in Amman with iconic Turkish artist Fahrelnissa

AMMAN — In a fast-paced world where motherhood has become an underrated role, artist Nissa Raad celebrates the core of what it means to be a