You are here

Fighting hate with humour

By Sally Bland - Oct 29,2017 - Last updated at Oct 29,2017

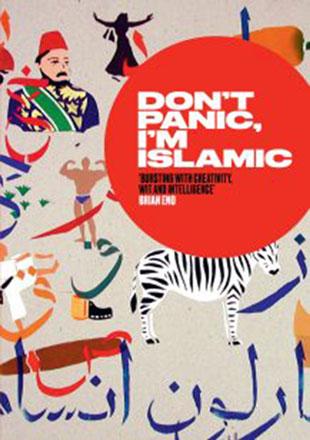

Don’t Panic, I’m Islamic

Edited by Lynn Gaspard

London: Saqi Books, 2017

Pp. 181

With the election of an overt racist to the presidency of the most powerful country in the world, statements and policies inspired by Islamophobia have reached such ridiculous heights that one does not know whether to laugh or cry. As reflected in the title, the 34 contributors to this book opted for the former, taking humour as their “weapon” of choice to dispel stereotypes about Muslims and outsiders. Donald Trump is not often named, but it is clear that his “Muslim ban” provoked this timely publication, though the thinking of the contributors has certainly been evolving over a longer period.

All of the essays, poems and stories in “Don’t Panic, I’m Islamic” are creative, polished and daring; many of them are hilarious. The same can be said of the graphics, which are stunningly colourful in their celebration of diversity, and occasionally shocking and bizarre — an appropriate response to real events.

Arwa Mahdawi mixes irony with puns in “A Personal Guide to Extreme Vetting”, which she suggests does not target Muslims, but must be “designed with animals in mind”. (p. 3)

Her guideline, “What’s in their pantry?”, is priceless: “A predilection for extra virgin olive oil is a sign that someone might be thinking a little too much about the afterlife. You are what you eat. Watch out for foodamentalists”. (p. 5)

Karl Sharro’s satirical piece on getting a visa to the US shows that there was always extreme vetting. For his part, Omar Hamdi satirises pseudo-studies about Islam and disingenuous Muslim responses to their conclusions: “The most important command in Islam is to be angry. And it is such a universal way of life — you can be angry about anything you like — Israel, Syria, silly cartoons… This is what makes it superior to western culture, where people are only allowed to be angry about unimportant things, like Oscar winners or dead gorillas.” (p. 38-9)

Palestinian Sayed Kashua writes tongue-in-cheek of the advantages of Trump’s presidency. Having left the insecurity of West Jerusalem for the tranquility of the American Midwest, he began to fear that “the sense of security that seemed to swaddle me in America would affect the quality of my writing, that no longer being exposed to unbridled racism would leave me no choice but to launch a career as the author of romance novels for juveniles. Now I regard these feelings with bitter irony: at long last, here comes an American president who issues boycott orders against Muslims, refugees and migrants… holding out promise that I will not lack subject matter for writing”. (p. 147)

These writers and artists would like to go beyond false dichotomies of “us” and “them”, to get on with their lives, but events intervene, as when Hassan Abdulrazzak comes to work at a Boston science lab on 9/11, only to be confronted by an American colleague asking: “So Hassan, can you explain Hamas to me?” “I feel all eyes are on me now. The room rapidly shrinks. I’m like Joseph K in Kafka’s ‘The Trial’, not quite sure what I am being accused of. I mumble something about Palestine and the occupation. My colleague looks disinterested.” (p. 86)

Some of the pieces are meant to be thought-provoking rather than funny, like Leila Aboulela’s short story exploring differences among Muslims about how to practise their faith. Moris Farhi spins a modern-day myth about defying megalomaniac leaders, dedicated to all those persecuted in Turkey for defending human rights and freedom of expression, while a poem in which Sabrina Mahfouz speaks as a mermaid is a poignant plea for more human understanding.

The very being of the contributors defies stereotypes as many of them have hybrid identities, and/or live between different countries and cultures. They are Iraqi-Egyptian, British-Palestinian, Iranian-American and so on. Negin Farsad calls it being a “Third Thing… a designation for people who straddle worlds, who may have a foot in every door yet their butt is hovering between door frames… I’m a Third Thing — Islam doesn’t explain me, Iranian poetry doesn’t explain me, and apple pie doesn’t explain me”. (p. 25)

Some of the contributors take on other kinds of difference, such as being gay, lesbian or black or a combination, while also being Muslim. Jennifer Jajeh’s story shows that whiteness is relative and in the eyes of the beholder. These are only highlights. Every piece is worth reading, every picture worth contemplating.

Admirably, Lynn Gaspard leaves her comments to the end. Foregoing the editor’s privilege of introducing a book, she allows the contributors to have their say first, magnifying their impact, instead of first explaining what the book is about. Noting Saqi’s thirty-year history of publishing alternative views, Gaspard concludes: “Where war or repression attempt to stifle creativity, the opposite can also be achieved. A steely resolve rises to give voices to the suffocated. And the more diverse these voices are, the harder it is to silence or restrict them.” (p. 168)

Related Articles

The Kindness of EnemiesLeila AboulelaNew York: Grove Press, 2017Pp.

There is an unusual, haunting love story intertwined with a coming-of-age novel, both infused with elements of myth, science fiction, philosophy and multiple cultural references.