You are here

Gilead is rotting

By Sally Bland - May 31,2020 - Last updated at May 31,2020

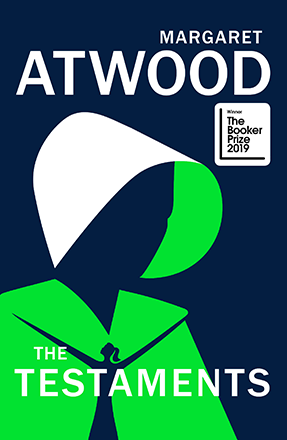

The Testaments

Margaret Atwood

London: Chatto & Windus: 2019

Pp. 419

“The Testaments” is the novel for which Margaret Atwood won the 2019 Booker Prize, jointly with Bernardine Evaristo. It is the sequel to “The Handmaid’s Tale”, Atwood’s dystopian novel about Gilead, a puritanical theocracy where women are prized only for their reproductive capacity, and otherwise systematically disempowered and abused.

Since its 1985 publication, “The Handmaid’s Tale” has had a rebirth in an acclaimed TV series and as a symbol of feminist resistance after the election of Donald Trump. Atwood was pleased with the TV series, not least because it “respected one of the axioms of the novel: no event is allowed into it that does not have a precedent in human history”, which makes the story all the more chilling. (p. 418)

Atwood was prompted to write “The Testaments” by readers’ questions about what happened after “The Handmaid’s Tale”, which ends inconclusively. In fact, one learns much more about Gilead in the new novel, how it was established by a coup against the US government; its spartan, war-time economy since fighting still rages in many areas; the rampant corruption in the ruling hierarchies from black market luxuries available only to the Commanders to widespread purges based on false witness; and the cover-up of murders, suicides, torture, paedophilia, and baby switching. Cruelty was always there, but in the beginning, there was idealism as well. Now, there are only power struggles and lies. “Beneath its outer show of virtue and purity, Gilead was rotting”. (p. 308)

Getting a more comprehensive picture of Gilead is a function of the narrators. As the title indicates, the first novel is told by a Handmaid, a nearly anonymous woman who stays in the house of a Commander and his Wife who cannot have children, until they acquire a child by virtue of her intercourse with the Commander. Per definition, the Handmaid is confined to the domestic sphere and acquires only limited knowledge of other goings-on via hearsay.

In contrast, “The Testaments” has three narrators. The first, Aunt Lydia, is the most powerful woman in Gilead whose career attests to the often-repeated maxim: Knowledge is power. Originally a judge who was captured after the coup, she decides, after an initial round of torture, to cooperate with the Commanders. With intelligence and deviousness, she manoeuvres herself to the top of the women called the Aunts, who organise the women’s sphere in Gilead, subject only to the approval of a top Commander. They train the young women in their charge to be suitable Handmaids or Wives for the Commanders or, occasionally, Aunts, and discipline them harshly for any infraction. Behind-the-scenes, they participate in important decisions concerning what status women will have, who they will marry, etc. And, crucially, they are allowed a library.

Aside from outright torture, the main tool of women’s disempowerment in Gilead is the edict forbidding them to learn to read and write. Ironically, in a state supposedly embodying the will of God, the Bible is kept under lock and key, accessible only to the Aunts, who are thus able to propagate their own interpretations.

Harbouring a desire for revenge for her forced conversion, Aunt Lydia’s idea of knowledge encompasses knowing others’ dirty secrets in order to manipulate them. Will she use her knowledge to bring Gilead down?

The other two narrators are young women in the process of becoming Aunts, one born in Gilead and one living in neighbouring Canada. While Aunt Lydia’s testimony shows what Gilead looks like from the insiders’ top echelons, theirs show how the system appears to a typical female citizen of Gilead and to an outsider, respectively. Atwood perceptively crafts their testimonies to fit their status: Lydia’s voice is mature, philosophical and cynical; Victoria’s is fresh and idealistic reflecting her aspiration to reform Gilead; while Jade’s reflects the attitude of a typical North American teenager rejecting all that Gilead represents. Eventually they are united in a plan to expose Gilead and bring about its end, spawning a hair-raising adventure that keeps the reader in suspense. “The Testaments” does answer many questions about the aftermath of the first novel, but also raises new questions.

Obviously, Atwood set out to warn against dictatorial regimes and fanaticism of all types. The novel graphically illustrates how the oppression of women poisons all spheres of society, warping men as well. It also shows how women’s complicity in their own oppression and rivalry with other women make their suppression easier. With their obsession about falling birth rates and the increasing number of deformed babies (due largely to unacknowledged environmental degradation), the Gilead Commanders resemble various white nationalist groups now on the rise in the West, especially the US. While the focus is on gender discrimination, “The Testaments” is a powerful argument against all types of discrimination. It also touches on the international issues of refugees, rampant consumerism and the environment, hinting at factors that can pave the way for dramatic, anti-democratic “solutions”.

But Atwood’s book is more than a warning. It is an erudite, beautifully written treatise on the power of a mother’s love, and also on how love and acceptance of differences can unite people who are not kin but who share common values. Like many other previous dystopian novels, she also highlights the importance of reading and books.

Related Articles

LONDON — British writer Samantha Harvey won the prestigious Booker Prize on Tuesday for her science fiction novel following six astronauts a

Everything I Never Told YouCeleste NgNew York: Penguin Books, 2014Pp. 292Celeste Ng has an original, captivating, writing style.

LOS ANGELES — Superhero Black Widow is a woman at the top of her game, and so is the actress who plays her — Scarlett Johansson is the world