You are here

Short, but complex

By Sally Bland - Nov 11,2018 - Last updated at Nov 11,2018

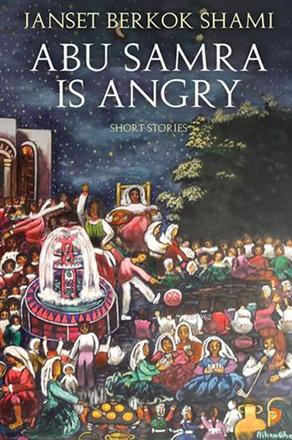

Abu Samra Is Angry: Short Stories

Janset Berkok Shami

Istanbul: Cinius Yayinlari, 2018

Pp. 268

Peopled with unusual, often idiosyncratic, characters and vibrantly described scenes, Janset Shami’s short stories are a delight to read but not because they necessarily give a rosy outlook on life. On the contrary, Shami often delves into the dark side of things, exploring people’s obsessions and unspoken motives. But whether written in an optimistic or pessimistic tone, all her stories are told from an unexpected angle which captures the reader’s imagination.

This book is the second collection of Shami’s short stories to be published in English. It contains eighteen of her tales written at different times in the course of her almost six-decades-long writing career. The volume is especially attractive as the cover displays a painting by Jordanian artist Riham Ghassib, depicting the traditional foods and popular activities of a large, open-air, Ramadan iftar. The painting is referred to in a story titled “Abu Samra Is Angry” which gives the collection its name. Ironically, in contrast to the painting’s subject matter, this story is about a man who has worked so hard to be “a thoroughly modern man” that he has lost all connection to his Arab heritage and to happiness as well.

“Abu Samra Is Angry” is told in the first person, as are over half of the stories. This narrative style gives the reader access to the character’s mind, and many of them are quite introspective, questioning not only others’ actions but their own. Such introspection is not always productive however. The young man in one story thinks carefully over everything he does, big and small, but is ill-prepared to make the most important decision in his life.

The stories are set in a variety of places: Two are in Turkey where the author grew up. Three “have no country” as she says in the preface. The rest are set in the Middle East, mainly Jordan, moving from refugee camps and modest neighbourhoods to middle class and wealthy homes in Amman and Irbid. About half the stories involve Palestine, mainly via displaced Palestinians living in Jordan and their offspring. One story is set in Nablus and considers the psychological effects of living in a place where death is ever-present, and where one’s killer, if Israeli, would never be held accountable.

The stories are short but not simple. The themes are varied, and most of the stories touch on more than one theme. Conflicted family dynamics are at the heart of several stories. In one, a young girl discovers the depth of her parents’ incompatibility in the run-up to her younger brother’s circumcision, making her question the whole idea of marriage and parenthood. Friction in other stories is caused by a man in the family having married a foreigner who does not adapt to life in Jordan, but most often marriage problems are seen as caused by the husband’s lack of consideration or real interest in his wife.

There are, however, happy families, such as the mother who creates marionettes with her children and the full support of her husband, perhaps reflecting Shami’s own experience with the marionette show she presented on Jordan Television for many years. There are also shining examples of families who love and care for each other, such as the story where a blind girl suggests to the blind man she loves that he marry her sighted sister instead, since they would better manage one of them could see, and her sister would be better off because he is from a wealthy family.

Several stories address how people deal with tragedy, how they fare when trying to cross class boundaries, or the masks they wear for various purposes. Many stories convey local customs, or recreate the scenery of old neighbourhoods of Amman, which are no longer the same, giving these stories a kind of nostalgia which they may not have had when written. The conflicts in the stories are not always black-and-white; some characters’ motives remain murky; and many stories end in an ambiguous way, leaving readers to draw their own conclusions.

Shami’s style is distinctive, and her imagery is original and sometimes jolting. At a fateful wedding, the bride compares the cake to a rocket: “It might take off and carry away our wedding vows.” (p. 229)

There is lots of personification as objects come alive in Shami’s charming descriptions. Emotions are described in visceral terms, as when one character describes facing a potentially humiliating situation: “Some organs inside me switched positions. They went sideways, then turned upside down. That upheaval made the decision for me.” (p. 243-4)

Taking her inspiration from real life and ordinary people — if such a species exists, Shami digs below the surface to unearth the psychology behind human behaviour. By slightly heightening or exaggerating reality and describing it in vivid language, she creates stories that are both fantastic and credible, which is no small feat.

Related Articles

This book, like the “two novels, six short story collections and a book about her friendship with the artist Princess Fahrelnissa, her mentor” by the same writer, is sure to help her reach immortality, in the process making the reader privy to a rich life and sharp, inquisitive mind that could be the envy of many, tens of years younger than her.

In her short story collection "A List to Remember", Turkish Amman resident Janset Berkok Shami illustrates the personal repercussions of the political and social upheavals to which people in this area have been subjected.

Fahrelnissa and I: A MemoirJanset Berkok ShamiIstanbul: Cinius Publishing House, 2016Pp.