You are here

‘A strange education in the value of life’

By Sally Bland - Aug 30,2015 - Last updated at Aug 31,2015

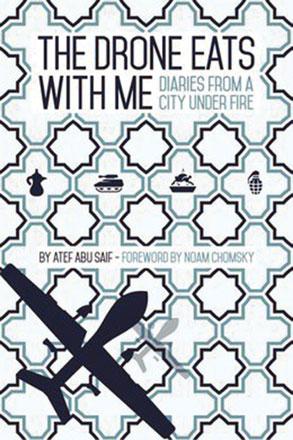

The Drone Eats With Me: Diaries From a City Under Fire

Atef Abu Saif

England: Fasila/Comma Press, 2015

Pp. 250

Statistics are mandatory when documenting war crimes, but Atef Abu Saif is aware of their dulling, dehumanising effect when the number of casualties mounts dramatically, as it did in Gaza in the summer of 2014. To convey the reality of the 51-day Israeli assault, he chooses a different approach. Though a writer and political commentator, he puts himself in the shoes of all Gazans and records his daily experience and feelings.

When writing about an Israeli attack, he names the victims by name, to remind that a real human life is lost — a precious past, a throbbing present and an unfulfilled future. His unflinching prose is complemented by Janice Hickman’s eloquent pen-and-ink drawings.

The imagery of the book title “The Drone Eats With Me” is poignant and immediate. Drones and their whirring sound are omnipresent, a constant reminder to the beleaguered people of the tiny territory of Gaza that they are never out of reach of the Israeli arsenal; they can never relax and go about their lives; they are occupied by remote. Whether on reconnaissance or a bombing mission, drones invade even the private sphere, the home, the dinner table, generating pervasive fear and a feeling that death is imminent. “Death becomes a normal citizen in your neighbourhood.” (p. 147)

Abu Saif’s idea that the drone eats with him captures this fear and insecurity, but also describes the Israeli conduct of war. Drones don’t just kill, they devour their targets, spitting out random body parts. F-16s don’t merely bomb select targets, they gobble up homes, farms, public buildings, whole neighbourhoods, leaving only rubble in their wake, depriving people of loved ones, shelter, livelihood, all signs of culture and beauty, and their already limited freedom of movement.

The diaries are not only about death and destruction, but give a sense of how life goes on in the worst of circumstances. Describing his daily routines, Abu Saif paints a picture of the struggle to obtain food when shops are closed, refrigerators don’t work and farmers don’t dare enter their fields to harvest crops. He describes the struggle to sleep amidst the clamour of explosions, and the struggle to refill water tanks and recharge phones and laptops during the few hours of electricity that are granted.

Then, there is the struggle to keep one’s sanity in the midst of insanity, the dilemma of whether to celebrate Eid or a birthday when so many people are dying, or of deciding whether to move to a safer location, knowing that any place can be hit. As he observes, “I know in my heart that I live by chance, and when I die it too will be by chance.” (p. 34)

“Passing the time is the most challenging of tasks in such moments, a true mission: to wrap distraction around your panic,” trying to keep a semblance of normalcy for the sake of one’s children. It is also challenging for Abu Saif to answer his children’s probing questions, but their noise and activity level are great distractions: “They upstage the sounds of the terrible world outside.” (p. 30)

As Abu Saif moves cautiously around to visit relatives and friends, he shares many personal stories and his impressions of important landmarks in Gaza, their history and how geography changes under the impact of war. The small details and personal stories he conveys serve to re-humanise Gazans. There is the man who sends his family to a safer place but remains in his house to feed the birds in his aviary.

Another man, whose house was completely destroyed, clears a spot in the rubble and pitches his tent. A deaf boy, whose broken hearing aid will not be repaired until the war ends, wanders in confusion. Families crowd together to share their house with the displaced who cannot even fit into the UNRWA school shelters.

The war is “a strange education in the value of life”, spurring new meditations on the meaning of life, death, love, happiness and hope. (p. 173)

Abu Saif asks some hard questions: “Who will convince this generation of Israelis that what they’ve done this summer is a crime? Who will convince the pilot that this is not a mission for his people, but a mission against it? Who will teach him that life cannot be built on the ruins of other lives? Who will convince the drone operator that the people of Gaza are not characters in a video game?” Past experience gives Gazans little reason to await help from the international community. In the author’s view, they have “only hope and their own resilience to fall back on”. (pp. 66-7)

Reading this book, one is further incensed that, more than a year later, the much-needed rebuilding of Gaza has hardly begun.

Related Articles

Gaza as a MetaphorEdited by Helga Tawil-Souri & Dina MatarLondon: Hurst & Company, 2016Pp.

The Book of Gaza: A City in Short FictionEdited by Atef Abu SaifGreat Britain: Comma Press, 2014Pp.

GAZA CITY, Palestinian Territories — They may not be able to leave Gaza without Israeli or Egyptian permission, but their photos can. T