You are here

Students are still using tech to cheat on exams, but things are getting tougher

By USA Today (TNS) - Aug 17,2019 - Last updated at Aug 17,2019

AFP photo

By Dalvin Brown

In many ways, cheating on high school and college exams used to be a lot harder than it is nowadays.

What used to take an elaborate plot to discreetly spread answers across a classroom can now be done with a swipe on a smartwatch. You used to have to steal the answer key or have a cheat sheet hidden around your desk.

Now, smartphones can be disguised as calculators, information can be spread invisibly via the airwaves and tiny earbuds allow students to listen to content transmitted from a smartphone in their backpack across the room.

The self-identified student cheaters we reached out to wouldn’t go on the record to discuss these behaviours (for obvious reasons). However, Twitter is a hotbed for discussion on the topic and smartwatches are a fan favourite as a convenient loophole to classroom smartphone bans.

“An Apple Watch is the go-to way to cheat on any exam. Hands down,” Tweets @too_Coziey in December 2018. “I bought an Apple Watch just to cheat on exams in [high school],” writes @Shymyafaith.

“My teacher collects phones during exams so I brought two phones and an Apple Watch. I will cheat on my exam, i don’t care if it kills me,” writes Twitter user @Wontonpx.

There are even online instructional videos and countless digital forums that teach students how to cheat on tests using their gadgets.

Technology enthusiasts often tout the latest innovations as tools to help students feel more engaged in the classroom. They encourage teachers and schools to adapt to the shifting tech landscape and instructors and institutions often follow suit, introducing Echo Dots and smartwatches to campuses in recent years.

While the gadgets have utility in educational environments, they also open pandora’s box, allowing students to pay less attention in class and shortcut their education — aka cheat.

“Technology presents new ways for students to do things that they’ve always been doing which is avoid doing the work themselves,” said David Rettinger, president of International Centre for Academic Integrity and instructor of psychological sciences at the University of Mary Washington.

“Forever, students would go to a book and copy things for a paper. Copy and paste plagiarism is as old as reading and writing, but now it’s so much easier. You don’t even have to leave your desk to do that. The bar has gotten much lower.”

In other words, cheating is nothing new, and students have been taking notes on their devices, getting notifications during tests, texting their friends for answers and sending photos of exams to their classmates for years.

However, one of the latest, widespread forms of cheating in the classroom involves students using auto-summarise features in programmes like Word to pass off computer-generated essays as original work.

Summarising tools can also be found on the internet. They take the most important information from a large text and generate a shorter version that isn’t easily picked up by anti-plagiarism software, according to Teddi Fishman, the former director of the International Centre for Academic Integrity.

She works with educators, students and administrators to identify integrity vulnerabilities, and taught at the State University of West Georgia and Clemson University.

What makes today’s cheating landscape even more dire is that “teachers are so overworked” Fishman said. “A lot of them are not tenured so they may be working at two or three universities to make ends meet. They just don’t have time” to double-check if they suspect a student of cheating.

Along with the auto-summarising tools, technology now enables students to buy “bespoke essays” from third parties overseas. These so-called “essay mills” don’t just let students buy one assignment. They’re contracting someone to write all their assignments for a semester or even a year.

If it’s an online class, “You can pay somebody in another country to take that course for you. If you do an easy online search for ‘take my online class,’ you see sites where someone can log in, take the class and you can get the credit for it,” Fishman said.

“That’s a danger for all of us. Imagine if your nurse paid someone to take classes for them.”

The Higher Education Opportunity Act of 2008 requires institutions to verify the identities of remote students by using at least one of the following methods: a secure login and password, proctored exams or other technological practices to accurately identify a person.

In many cases, the use of a secure User ID and password that can be easily exchanged with others and proctored exams are effective only if the instructor actually knows what the student looks like. However, tech such as typing-style verification and speed checks may help to curb cheating in e-learning situations.

Rettinger, who is also an associate professor of psychological science, has started giving his classes shorter exams, which cuts down on the time students could spend trying to figure out how to cheat.

“I’ve changed a lot of my assessment to be much shorter, lower-stake assessment rather than big exams. [So] students feel less pressure to cheat,” Rettinger said.

“When you have a test and it’s worth a lot of points, a student is going to put a lot of work into either studying or cheating,” he said. “If it’s a quick test, there isn’t as much time to set up those structures. You’re not dumbing down the material. I’m just testing more frequently.”

The University of Mary Washington and many others use a student-run honour codes to discourage cheating where the student body self-polices to create a social sanction against being dishonest.

Teachers also use tools like the plagiarism-checking software Turnitin to sniff out academic dishonesty. In March 2019, Turnitin released a piece of software called Authorship Investigate, which creates a digital fingerprint of a writer’s writing style so teachers can detect changes over the course of the semester to detect “contract cheating”.

Alexis Redding, a lecturer in the Higher Education Programme at Harvard who studied cheating, warns that if instructors don’t go through those types of plagiarism reports with students, they “become confused about what they’re doing right and what they’re doing wrong”.

Some institutions and departments across the country mandate that students submit all essays through plagiarism detection programmes.

“By the time you try to figure out how to outsmart the people who want to cheat, you’ve already lost the battle,” said Howard Gardner, a research professor of cognition and education at the Harvard Graduate School of Education.

Gardner said instructors and parents should help students understand “why one shouldn’t cheat and why it’s destructive to them”.

Related Articles

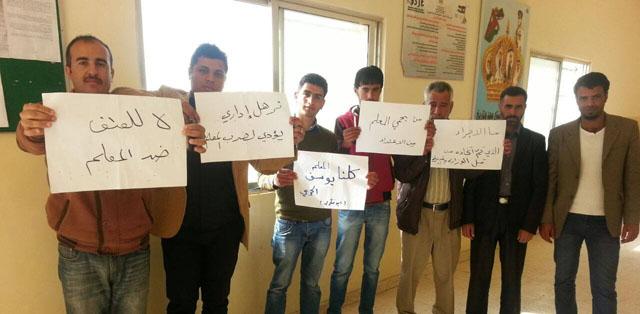

A teacher in Jiza District was beaten by a group of six students on Tuesday, according to the Jordan Teachers Association (JTA).

AMMAN — A video went viral in Jordan on Tuesday featuring a man announcing the answers to the General Secondary Education Certificate

The Education Ministry’s recent list of instructions to teachers is “improper in style and content”, the Jordan Teachers Association (JTA) charged on Tuesday.