You are here

Writing in a half-suspended state of war

By Sally Bland - Aug 16,2015 - Last updated at Aug 16,2015

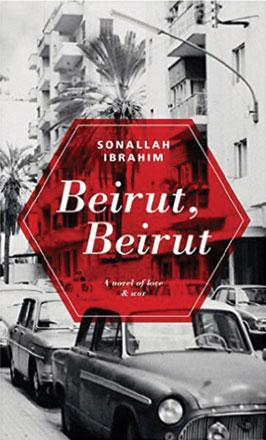

Beirut, Beirut

Sonallah Ibrahim

Translated by Chip Rossetti

Doha: Bloomsbury Qatar Foundation Publishing, 2014

Pp. 345

“Beirut, Beirut”, first published in Arabic in 1988, and now translated into English, is billed as “a novel of love and war”, but the bulk of the text is factual. In style and content, it showcases the most distinctive features of Egyptian intellectual Sonallah Ibrahim’s writing: his political engagement and his modernist technique.

In the 60s and especially during the five years he spent in Egyptian prisons for being a communist, Ibrahim broke with the prevailing effusive literary style in favour of short sentences and stark descriptions of physical reality, including its most mundane details. Influenced by Hemingway, among others, he tried to convey real experience by describing it very directly and graphically, without euphemisms or circumvention. In novels such as “Zaat” (English edition, 2001), he interspersed his narrative with news headlines and reports to posit his characters’ lives in their socioeconomic context, and expose corruption, consumerism and the harmful effects of Western and Israeli intervention.

These devices produce a “you-are-there” effect that is apparent in “Beirut, Beirut”.

The story is told in the first person by an Egyptian novelist, presumably Ibrahim himself, who arrives in Beirut in November 1980, with a manuscript he is seeking to publish, only to find that an outbreak of violence will make his task more difficult. As he moves around West Beirut and converses with old and new friends, one gets a sense of the political and security situation, and how it is to live in a war that is not over but only “managed” by those with influence. Not only is the danger of bombs and kidnappings pervasive, but there is a general lack of trust; one must always be wary, even of friends. The novelist takes all this in stride, calmly recording his impressions without emotional frills. His private moments with an intriguing woman are similarly described.

With the publishing house that he thought would take his manuscript in jeopardy, he finds another source of income, writing the voice-over for a film about the civil war. Conscientious about doing a good job, he goes through a comprehensive dossier about the causes and evolution of the war that he relates in detail, making the reader a partner in his research. In reviewing events, he highlights the class and colonial origins of the explosive sectarian system, ever aware of the costs to ordinary people as when he speaks of the number of dead and wounded: “not one of them carrying the name of one of the families that started the fight and that profits from the victims…” (p. 64).

Though much of Ibrahim’s account is a series of quotes from various news sources, and he doesn’t editorialise, his point-of-view can be discerned from which facts he presents and how he juxtaposes them. For example, there are extensive quotes from the testimonies of survivors of the massacre in Tel Al Zaatar refugee camp. In another passage, hypocrisy is exposed when a headline quoting President Ford as saying that the US “will do all it can to preserve freedom and democracy in Lebanon” is followed by a quote from The New York Times about Western arms flowing into Lebanon to the right-wing militias. (p. 134)

“Beirut, Beirut” is the testimony of a keen observer of politics and human behaviour.

Paradoxically, though Ibrahim’s writing seems emotionally detached, one feels that he really cares about the victims of the war, i.e., his modernist style succeeds in conveying his political message. One also learns a bit about the political economy of the publishing business in Lebanon, at least at that time.

Related Articles

This is a new translation of Egyptian writer Sonallah Ibrahim’s ground-breaking novel, “That Smell”, which was first published in Arabic in 1966, immediately banned and dismissed by at least one prominent Egyptian literary critic for the “vulgarity” of its physiological descriptions.

Committed to Disillusion: Activist Writers in Egypt from the 1950s to the 1980sDavid F.

The Palestinian Novel: From 1948 to the PresentBashir Abu-MannehUK: Cambridge University Press, 2018Pp.