You are here

British art historian traces origins of Madaba Map

By Saeb Rawashdeh - Jun 18,2022 - Last updated at Jun 18,2022

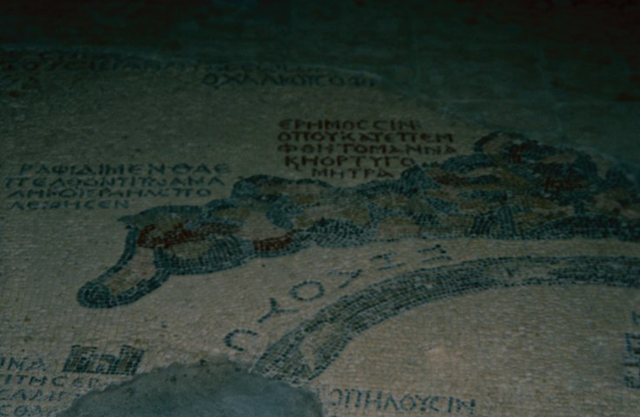

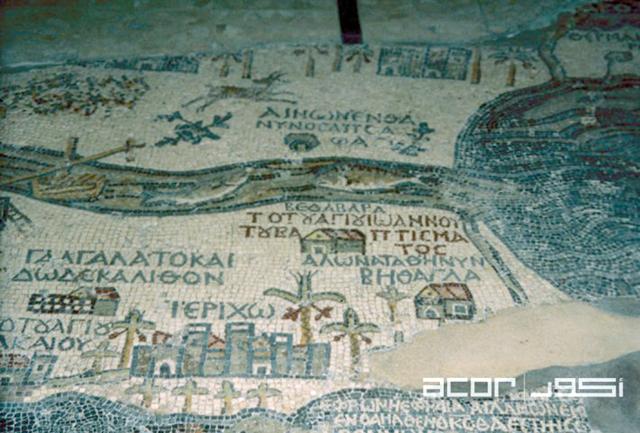

A fragment of a 6th century AD Madaba Map at St George Church in Madaba (Photo courtesy of ACOR/Rami Khouri Collection)

AMMAN — The Madaba Map in the St George Church, 30km southwest of Amman, can be traced back to the mid-sixth century AD, according to British Art Historian Beatrice Leal.

“We don’t know the exact date of the Madaba Map. It is likely that there was once a dedicatory inscription that could have given this information, but it’s not in the surviving areas of mosaic,” Leal said in an e-mail interview with The Jordan Times.

Leal, who received her PhD from the University of East Anglia, determined the date of the map by comparing it to similarities with other mosaics nearby, like at the Church of St Lot and Procopius at Khirbet Al Mukhayyat.

“Assuming that date is roughly right, there’s a bit more we can say about the circumstances of production, and here I’m drawing on Diklah Zohar’s findings on sixth-century mosaic practice, as well as my own research,” Leal said.

She noted that in the sixth century AD, mosaicists worked as individuals or in small groups, which were sometimes family-based. They would come together as larger groups for big commissions, but did not operate as formally organised workshops.

“Mosaicists tended to work within their local area, in which case they most likely came either from Madaba itself or from the surrounding countryside,” Leal said.

“The large number of mosaics found at sixth-century sites in Jordan — or even in the diocese of Madaba alone — shows that there was a good living to be made in this craft, and the reasonably frequent finds of mosaicists’ signatures show their literacy, their pride in their work and a degree of control over the details of the compositions,” Leal added.

Leal said the architectural depiction of towns on the Madaba Map vary, adding that some towns and villages, particularly near the edges of the map, are shown as generic and identical gate-towers regardless of if these buildings had these structures.

Others re-use a small number of stock forms, mainly towers and basilicas combined at varying angles, to give an impression of individuality, without any clear connection to the appearance of the place.

She said that for other towns and cities, the representations seem more “carefully thought out”.

“For example, Karak is shown on top of a rocky hill, as it is, and the famous image of Jerusalem includes its central colonnaded street and freestanding column,” she said.

“The places which the Madaba audience [and the mosaicists] would have known more about are shown in more detail. But accuracy may still not be quite the right term to describe this. Even in the case of the most detailed depiction of Jerusalem, I don’t think that every building represented can be matched with a historical structure,” Leal added.

Furthermore, there are more than 150 inscriptions on the surviving areas of map, she continued, which is only a fragment, maybe as little as a fifth of the original design.

“Even just taking the surviving portion, the density of script is unique; I don’t know of any mosaics from anywhere else in the Byzantine period that come near it. The inscriptions mostly give names of places, and sometimes things that happened there,” Leal said.

Related Articles

AMMAN — Mosaics decorated some of most prestigious buildings in the Ummayad Caliphate: Bath houses, mosques, palaces and private villa

AMMAN — The sixth-century mosaic map of the Holy Land is not only an example of the Byzantine period artistry but a primary historical

AMMAN — Mount Nebo holds a special place in the heart of mosaicist Franco Sciorilli, being as it was the base of operations for the late Fat