AMMAN – There are two types of weapons in the Bronze Age warfare: ceremonial weapons of rulers and members of the political elites, and weapons that were actually used in the combat.

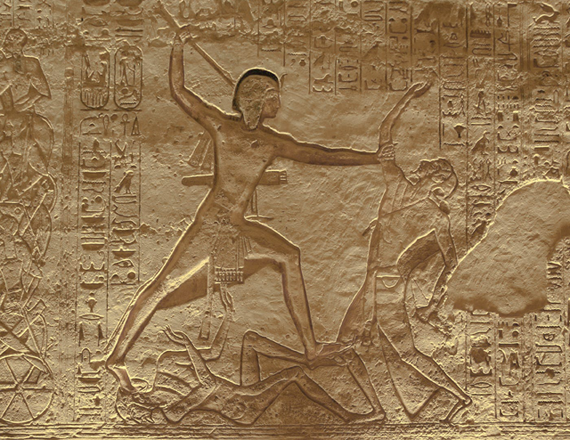

A mace was a popular weapon in the Egyptian Middle Kingdon and on many monuments, we can see the motif of the Egyptian pharaoh smiting enemies with a mace. The mace was a very popular weapon for hand-to-hand combat.

Human remains found in different necropolis can give us some answers how people lost their life in the Bronze Age. The physical evidence of wounds and casualties suggest the frequency with which various types of weapons were actually employed tobloody effect, as well as indicating exactly how they were intended to be used.

The main obstacle to this approach is the small size of the excavated sample, noted Aaron Burke, an American professor.

"Mortuary evidence from the Levant and neighbouring regions provides, nonetheless, considerable insight into the mechanics of warfare in the Middle and Late Bronze Ages," Burke said, adding that one of the best-known examples of military casualties during this period is a collection of corpses from Egypt dated to the end of the Eleventh Dynasty.

Fifty-nine mummified Egyptian soldiers found in acommunal tomb near Deir Bahri were identified by Herbert Winlock (1945) as troops of Nebhepetre Mentuhotep II (ca. 2,043–1,992 BC), and most of these soldiers sustained mortal wounds from arrows, many of which appear to have had ebony heads, although a few of the arrowheads were apparently of the blunttype, Burke explained, noting that entry wounds on many of thesoldiers indicate that arrows were fired from above, as if during a siege.

"Four of the soldiers also sustained head wounds prior to their participation in a final battle, and three of these suffered injuries to the left sides of their heads, indicating that their attackers were right-handed. In addition to arrow wounds and head traumas inflicted by blunt objects, Winlock observed frontal wounds on fourteen other soldiers that were probably inflicted by stones (if not sling projectiles) apparently hurled from above," Burke elaborated.

It also appears that a number of the soldiers were not immediately killed by arrow wounds but were finished off with blows to the head by blunt objects such as clubs or even maces, though it is possible that these final wounds were inflicted by objects thrown or dropped upon them from the town wall.

Winlock speculated that soldiers were left to rot and many were missing body parts because carrion birds feasted on them.

He concluded that these soldiers were probably involved in a siege on Herakleopolis under Mentuhotep II.

"One clear example from the Levant of an individual killed under similar conditions comes from Late Bronze Age Ugarit, ca. 1,300 BC. Theremains of a man between eighteen and thirty yearsof age were recovered. He had been killed by an arrow that pierced his chest from above and infront of him, which became lodged in his spinewithin his chest cavity. The arrowhead was so deeply embedded that it was impossible to remove it," Burke said.

Another slain Egyptian from the end of the Middle Bronze Age further demonstrates the effectiveness ofthe battle ax and the injuries that could be sustainedfrom it.

The remains are those of the Theban king Seqenenre Tao II (Dyn. XVII), who was found at Deir Bahri and dated to ca. 1,550 BC.

"This Theban ruler was apparently killed by five blows to the head [no other wounds were found on the body]. At least three of the blows are thought to have come from an Asiatic-type of battleax. He was presumably killed during an early attemptby the Thebans to expel the Hyksos from Lower Egypt. The other wounds to his head were probablycaused by a spear or sword, and in one case by a club or the handle of an ax or spear," the historian explained.

To these casualties of war, it is possible to add several others known from burials in northern Mesopotamia and the Levant.

At Tuttul (Tell Bi‘a), for example, the remains of eighty individuals buried in a mass grave were discovered in layers of the central mound dated to the reign of Samsi-Adad, ca. 1,719 – 1,688 BC.

The corpses were laid hap hazardly in a single grave and it appears to be possible to distinguish wounded soldiers from civilians.

Similar evidence of carnage comes from the siege of Ebla in the northern Levant at theend of the Middle Bronze Age, Burke said, adding, "Here a mass grave dating to ca. 1,550 BC was recently discovered on the outside slope of the rampart to the east of the Area EE fortress."

In the southern Levant the only Middle Bronze Age site that has produced similar evidence of persons slain in combatis Shechem (Tell Balatah).

"Here six skeletons, two of them fully articulated, were found on the inner steps of the East Gate among fallen bricks and the destruction debris dated to the end of the Middle Bronze Age," Burke said.

This array of Bronze Age casualties of war, mostlyfrom the Middle Bronze Age, makes it possible todraw some important conclusions concerning warfare of this period.

"The siege warfare was as frequent and as dangerous as has been suggested based on both references among the Mari texts and Egyptian reliefs. Although the sample size is small, the nature of the wounds inflicted on the corpses suggests that sieges and not pitched battles were responsible for many of the casualties incurred by armies in this period. From these casualties, we can also determine the types of weapons employed inbattle during the Middle Bronze Age," Burke concluded.