You are here

No green pastures for Jordan's herders in times of climate change

By Mohammad Ghazal - Oct 15,2022 - Last updated at Oct 15,2022

Menwer Ibrahim, a livestock herder in the Al Majidiyya village, is seen posing in front of his sheep in this recent photo. Recent photos of a part of the 400 dunum area where the International Centre for Agricultural Research in the Dry Areas implements advanced environmental technology (JT photos)

- New rangeland restoration technology provides hope, but efforts must be increased

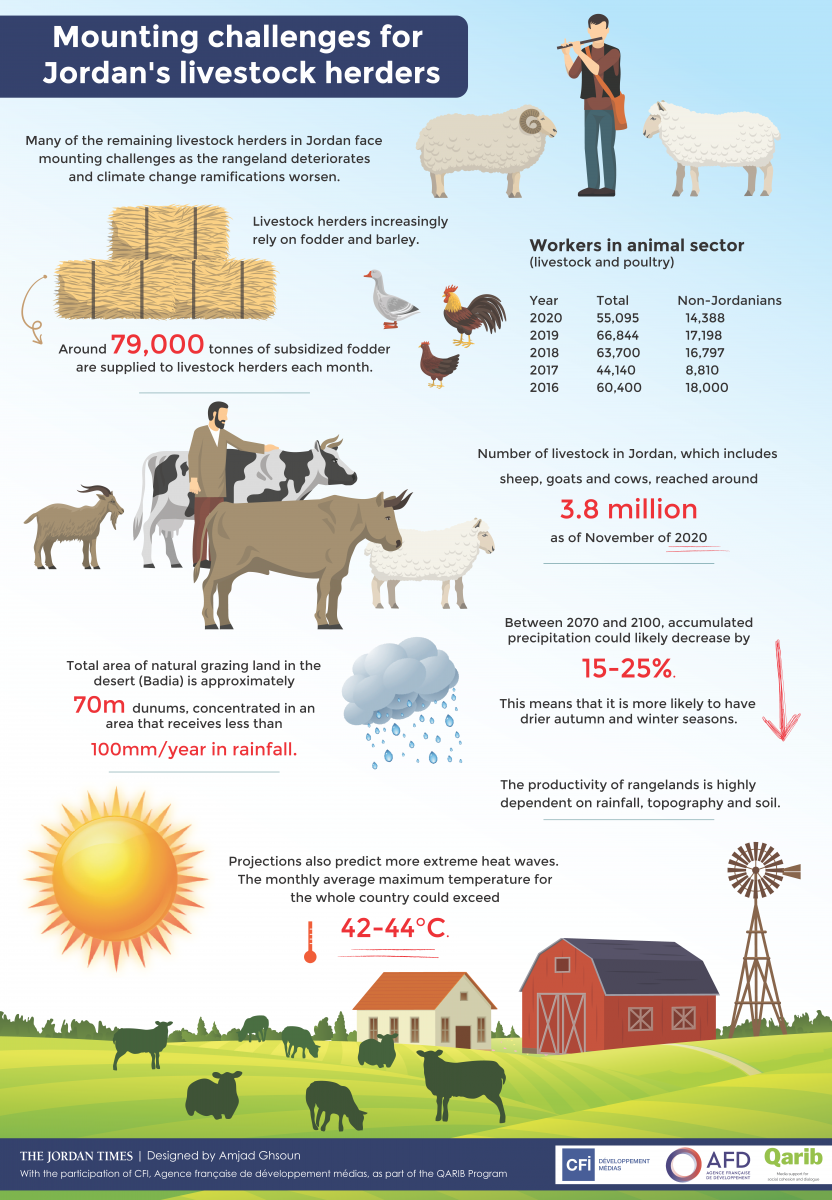

- Accumulated precipitation could decrease 15-25% by 2070-2100

- Impoverished people in Jordan will disproportionately bear the burden of climate change

- Monthly average maximum temperature for Jordan could exceed 42-44°C by 2070-2100

- Marab technology helps increase barley production by 10 times

- 79,000 tonnes of subsidised fodder per month supplied to livestock herders

- 25% of Jordan’s poor live in these rural, agriculture-dependent areas

- Out of 70 million dunums of rangeland, only 1 million dunums are considered natural reserves

AL MAJIDIYYA — Menwer Ibrahim, a livestock herder in the small village of Al Majidiyya, 60 kilometres southeast of Amman, said he considered quitting herding livestock several times. Like many livestock herders in the area, the job is Ibrahim’s only source of income, and his only marketable skill, as he did not complete his education.

The 39-year-old said herding livestock became more difficult as time passed by as his village, once an edenic location for herders full of natural rangeland and vegetation, has transformed into an arid piece of land, making the livelihood of livestock rearing almost impossible due to erratic rainfall, rising temperatures and declining precipitation.

“When I started raising livestock almost 20 years ago, some parts of the land were covered with grass, vegetation and several types of shrubs. As the rain became less, and temperatures soared, the area became unpopular for livestock herders,” he told The Jordan Times.

As the vegetation receded, Ibrahim resorted to buying fodder and barley from the Agriculture Ministry and other Jordanian barley farms to feed his cattle, but this costly necessity pushed many of the village’s herders to quit the business.

Many of the area’s remaining herders, like Ibrahim, are facing mounting challenges as the rangeland deteriorates, a source at the Ministry of Agriculture told The Jordan Times.

“Climate change ramifications have already affected natural rangeland in Jordan, and cattle herders heavily rely on subsidised fodder…We have to admit that negative effects of the climate crisis started to harm our natural rangelands years ago, and increased the burden on herders. However, we will continue to provide fodder and loans when necessary to support this vital sector,” the source said. According to the Ministry of Industry and Trade, around 79,000 tonnes of subsidised fodder are supplied to livestock herders each month.

Figures by the Department of Statistics (DoS) indicate that the number of workers in the animal sector, which includes livestock and poultry, has been declining and fluctuating since 2008 when the overall number of workers reached a high of 97,110.

In 2009, the total number of workers reached 80,240; in 2010, it reached 62,940. According to the official figures, the number was 57,550 in 2015, and in 2016 it reached 60,400, while in 2017 it stood at 44,190, in 2018 it was 63,700, in 2019 it was 66,844 and in 2020, the latest available figure, the number stood at 55,095 of whom 15,830 are Jordanian and non-Jordanian women, according to DoS.

The number of livestock in Jordan, which includes sheep, goats, and cows, reached around 3.8 million as of November of 2020, according to the DoS figures. In November 2015, the number of livestock was 3.530 million, in 2010 it was 2.992 million and in 2005 it was 2.474 million, according to DoS.

'Negative climate effects hurt livelihood'

Not only do livestock herders in the village suffer from rangeland degradation, but women also bear a significant portion of the burden.

In the village, many individuals rely on livestock breeding. With no proper public transportation and insufficient job opportunities in other fields, the situation has become difficult even for those who rely on raising goats and use their milk to produce some home-made dairy products such as yoghurt and Jameed, which is dried yoghurt used in Jordan’s national dish, mansaf.

Um Hussein, head of the Wadi Al Mataba Women Society, said that over the past few decades, many female livestock herders have quit the business.

“Women used to raise small numbers of sheep and goats, and they used to make Jameed [dried yoghurt used in Jordan’s national dish, mansaf] and other dairy products to support their families, but as rainfall declined and vegetation disappeared almost all of the women in the village sold their cattle, as it was very expensive to buy fodder. They ended up with no income,” she told The Jordan Times.

“We used to heavily rely on feeding our cattle with vegetation and shrubs in the area, but there is not enough rain anymore, which is very sad. To raise cattle, you need money for fodder,” she said.

The situation is no different for Abu Maen Shorofat, a livestock herder and a resident of the Al Dgheilah area in the Mafraq governorate.

“Almost 25 years ago, I used to feed my cattle from the natural rangeland in the area. I had more than 1,200 sheep and goats back then, but with the lack of vegetation, I started to sell them one by one to buy fodder and barley. Now, I have around 250 sheep and goats in total,” he told The Jordan Times.

'Bleak situation, requiring intervention'

President of the Jordan Environment Union Omar Shoshan told The Jordan Times that more efforts on a national scale are needed to address the issue.

“Hundreds of families rely on herding livestock, especially in remote areas where there are no jobs. Immediate intervention is needed to help rehabilitate degrading rangeland, as the impact of climate change is expected to worsen,” he said.

Jordan's Third National Communication Report to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) and the country's updated Nationally Determined Contribution to the UNFCCC anticipate climate change ramifications to affect various sectors in Jordan, and that impoverished people in Jordan will disproportionately bear this burden.

According to the third communication report, the total area of natural grazing land in the desert (Badia) is approximately 70 million dunums, concentrated in an area that receives less than 100mm/year in rainfall, as short thunderstorms and rainfall quantities are decreasing in the east and south until rainfall reaches 50mm/year or less. Of these 70 million dunums, only 1 million dunums are considered natural reserves.

“Natural rangelands are almost non-existent in Jordan anymore due to climate change and when there is heavy rainfall it affects the soil and what is left of small lands that have vegetation,” Shoshana said.

According to the report, Jordan’s natural rangelands play an important role in covering livestock feed requirements. In spite of the damage that they have sustained over the past five decades, they can cover feed requirements for two to three months without supplementary feeding, or 30 per cent of the feed requirement.

Currently, the remaining spots with vegetation distributed in various areas across the country do not cover their needs for more than 2-3 weeks, according to the Agriculture Ministry official.

Between 2070 and 2100, accumulated precipitation could likely decrease by 15-25 per cent. This means that it is more likely to have drier autumn and winter seasons, with the median value of projected autumn precipitation decrease reaching -35 per cent, according to the communication report.

Projections also predict that the monthly average maximum temperature for the whole country could exceed 42-44°C.

The productivity of rangelands is highly dependent on rainfall, topography, and soil. Rangeland feed productivity per unit is estimated at around 40 kilogrammes of dry feed per dunum in areas with 100-200mm of annual rainfall; and 100 kilogrammes per dunum in areas that receive more than 200 mm.

About 25 per cent of the total poor in Jordan live in these rural areas which depend mostly on agriculture and include livestock keepers, smallholder farm households, and landless former agriculturalists. Despite poorly motivated rural youth, agriculture remains an important employer of rural communities.

The National Climate Change Adaptation Plan of Jordan 2021 indicated that the increase in the evapotranspiration rate and the decrease in precipitation in drier systems, such as the arid and semiarid rangelands of Jordan, would reduce agricultural productivity.

Jordan’s National Climate Change Adaptation Plan 2021 indicated that several studies have proven the increased instance of drought events in Jordan. Drought severity, magnitude, and span will all increase with time, shifting from normal to extreme levels.

A Glimpse of Hope

To help rehabilitate the degrading rangeland and restore indigenous plants and shrubs in the village, the International Centre for Agricultural Research in the Dry Areas (ICARDA) started a project over a 400 dunum area in the village boundaries in 2016 using advanced technology to help villagers and livestock herders, said Mira Haddad Research Associate at ICARDA.

“Some of the technologies we implemented are called Vallerani system and Marab…These technologies helped take advantage of the rainfall in the area, and played a role in mitigating the impact of climate change by helping restore some indigenous plants and shrubs, providing vegetation and shrubs that livestock herders were able to benefit from,” she explained.

“Climate change affected the natural rangeland in Jordan. Human-induced activities made the situation worse…we used science to help the herders, as with lack of vegetation, many have quit their profession,” Haddad added.

According to ICARDA, the mechanised micro water harvesting that occurs with the "Vallerani" tractor plow technology supports the rehabilitation of degraded rangelands. The Vallerani plow forms micro, water harvesting pits that are suitable for native shrub seedlings. This boosts vegetation recovery through both out-planted shrubs, and the emergence of local seeds.

The Marab-Water Harvesting Based Floodplain Agriculture technology conserves soil and water by reducing surface water and sediment losses from dryland watersheds. The technology is placed downstream in lowland floodplains, and ideally, it is implemented using an integrated watershed approach. In the present case study, the "Marab" is linked with two main upstream measures: Upland micro-water harvesting (the Vallerani system) and gully/channel measures (gully plugs).

The Marab is a local, downstream water harvesting measure in an integrated watershed context, which is affected by up and midstream users as well as applied land management practices. The technology diverts and spreads excess runoff over deep-soil flood plains. The technology comprises local gully-filling, the grading/levelling of seed beds, and the construction of a bund-and-spillway system, creating several compartments to benefit flood-irrigated agriculture.

Muhi El Dine Hilali, the scientist at ICARDA, said: “The Marab technology helped increase barley production 10 times when compared to areas where this technology was not implemented. The other technology helped restore some types of shrubs that are full of benefits for animals and human health as well.”

“The quality of meat and milk has improved, as livestock are now eating healthy shrubs that are full of nutrients, which are good for the animals,” he said. The technology has also been beneficial to the soil, he said, adding that there is now a need for increased conservation of the rehabilitated lands to prevent any violations.

Mohammad Alnsour, Natural Resources Manager at the Sustainable Ecosystem Development NGO, called for scaling up the project.

“More funding is needed to scale up the project to benefit other areas in Jordan. These technologies increase resilience to climate change ramifications and we need to see more of such interventions,” he said.

For scaling up such technologies, more efforts are required to enforce rule of law and prevent violations against the rehabilitated land such as overgrazing. There is also a need to conserve and protect such areas and possibly fence them to prevent any danger to the indigenous species, according to Nsour.

“These technologies have changed the life of livestock herders like Ibrahim, and we need to maximise their benefits for other communities,” Alnsour added.

Ibrahim said that he is thrilled by the use of these innovative restoration projects, and is currently leading a good life, able to support his direct and extended family.

His business is going well, he said, thanks to the new technology.

“The goats produce more milk. The sheep are healthier, as they eat local indigenous shrubs that are good and full of nutrients, and this is much better than the fodder and barley. I saved a lot of money as I now can rely on feeding the cattle from the grass and the shrubs in the area for several weeks, and this was impossible before," he said.

“I am happy, and I am not thinking of leaving the village or my profession anymore. Most of the goats have been giving birth to twins and even triplets, and now I have 300 sheep and goats. I am satisfied,” Ibrahim added.

The impact was also felt by several other herders in the area, according to Al Majidiyya Society President Mubarak Mufleh.

"Over the past 15-20 years many quit this profession and joined the public sector, but tens of herders in the village resumed the profession since the introduction of the new technologies and this is quite an achievement as the project is on a small-scale now and we are a small village," he said.

The project created 20-25 jobs for local communities to ensure the sustainability of the project including maintenance and logistical jobs. Around 20-30 herders in the village resumed the profession either full-timeor part-time and herders from nearby areas also benefitted from these technologies, Mufleh said.

'This content was prepared with the financial support of AFD under the Qarib programme implemented by CFI. This content is the sole responsibility of the author and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of CFI and AFD. The analysis, opinions, and views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of CFI or AFD. Thus, only the author's responsibility can be engaged.'

Related Articles

AMMAN — In a move towards sustainable agriculture, numerous farmers in Karak are now reaping the benefits of using treated water for fodder

AMMAN — The name “Bedouin” is derived from the term for nomadic desert or steppe dwellers (badawa).

Pastoral shrubs will be planted in the northern and central badia and rainwater harvesting projects will be implemented in the area under seven agreements signed on Tuesday to support livestock breeders.