You are here

From soldiers to builders: Studying military labour in Ancient Levant

By Saeb Rawashdeh - Jul 08,2024 - Last updated at Jul 08,2024

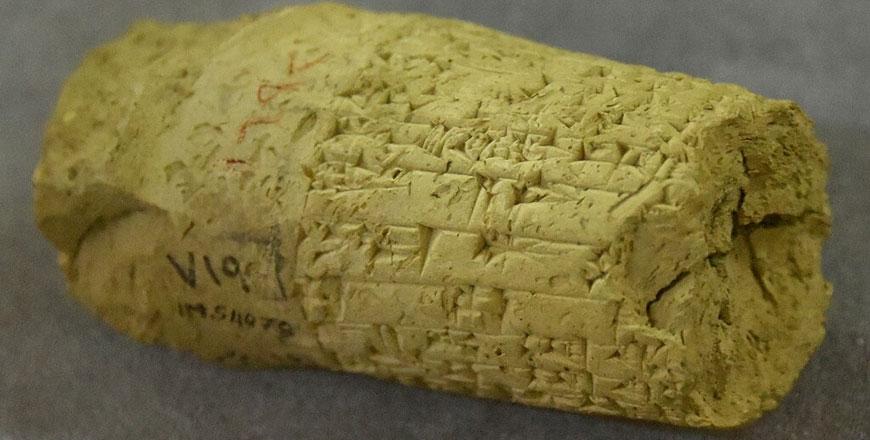

Clay cone of Nur-Adad, king of Larsa, 20th century BC (Photo courtesy of Museum in Sulaimaniya)

AMMAN — During the Bronze Age in the Levant, we witnessed the emergence of the first fortifications and city-states. The organisation of labour has been a significant factor in understanding the nature of the economic interaction between different states, regional powers and vassal statelets. In the Old Babylonian kingdoms, army undertook building and maintenance of fortifications and the part of the service in the army was to be involved in various labours. Ancient inscriptions describe the role of the military in organising construction works within the realm.

“Given the nature of army service, which was provided for the duration demanded, we may assume that these inscription simply noted the continuous labour over the course of the years required to build these fortifications,” said Aaron Burke, who received his PhD from The University of Chicago and whose area of academic interest are the Bronze and Iron ages in the Levant.

Corvee labour was another obligation to perform labour for a certain number of days per month or per year, and it was a public labour service. Strengthening and repairing dikes and cleaning irrigation canals were some of tasks, including the agricultural work on the fields that belonged to a ruler and ruling elites.

Construction, modification and maintenance of city wall were included in these tasks, Burke said, adding that for corvee labour, three months would be required.

Hired labour was another form of maintaining the local infrastructure and from inscriptions we are informed on wages paid to the workers who repaired city walls.

Nur-Adad of Larsa left the following account: “At that time, I built the great wall of Larsa like a mountain in a pure place. The wages of each worker were 3 ban of barley, 2 sila of bread, 2 sila of beer, 2 shekels of oil; thus they received this in one day.”

“Texts from Mari suggest that labourers could be sent to a settlement when it was urgent to rebuild a collapsed section of wall, as at Saggaratum where two hundred

labourers from Terqa were requested to complete the work in ten days. On other occasions, however, there appears to have been no immediate hurry to complete repairs,” Burke underlined, adding that unlike corvee labour that was limited to three months, hired labour could work much longer.

“Obligatory service, referred to as ilkum, in which a kingdom could obtain public service from its citizens, may have provided yet a fourth source of labour”, Burke continued, adding that during the Old Babylonian period, ilkum was identified as “service performed for a higher authority in return for land held”.

“It can be imagined, therefore, that during certain short periods in the life of each settlement members may have fulfilled their ilkum service by participating in fortification construction. Because of the nature of this labour, which on the one hand was integrally related to military activity but on the other was in the public’s interest, it is possible that those occasionally fulfilling ilkum in this manner laboured beside corvee labourers, soldiers, or hired hands,” Burke elaborated.

Women, slaves and children were also involved in labour if necessary.

Fortification building and maintenance required engineering knowledge so for these tasks rulers preferred military personnel. For the constructions of towers and protective walls specialised labour was necessary.

“There is no basis for assuming that any of the groups mentioned above, other than the army, would have had prior experience in fortification construction,” Burke noted, adding that the absence of textual evidence indicating the presence of specialised labourers among them or reference to any such titles supports this conclusion.

Related Articles

AMMAN – One of the main problems that historians and archaeologists specialised in the Bronze Age face is the lack of concrete historical ev

NASIRIYAH, Iraq — After war and insurgency kept them away from Iraq for decades, European archaeologists are making an enthusiastic return i

AMMAN — After a pandemic-induced break in active field work in 2020, archaeological work in Jordan’s Wadi Shuaib resumed in 2021, said Alexa