AMMAN — When 10-year-old Omran Taqi arrived in Amman with his family, the activity he missed the most was going to school.

Before he left Syria, Taqi was forced to skip school because of the violence in his hometown of Hama.

“In Syria, I could not attend classes because there was fierce shooting in my neighbourhood,” he told The Jordan Times.

A chance encounter in the capital, however, enabled him to go back to school and resume studying his favourite subject: history.

When the Syrian boy was sitting outside his family’s tent, located in a makeshift camp in the capital’s Khreibet Al Souk neighbourhood, he noticed that a number of children gathered in one tent carrying notebooks and bags.

“When I found out that the tent was a small school, I was over the moon and decided to join,” he added.

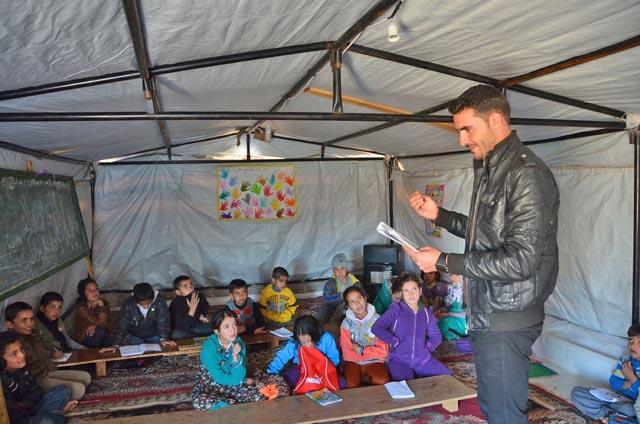

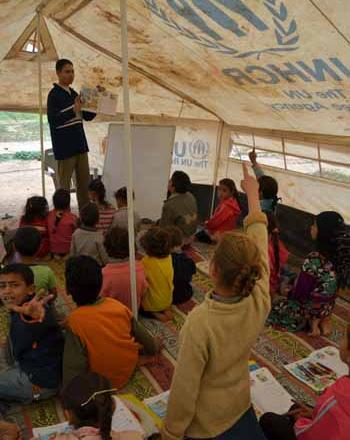

Taqi is one of 40 students aged between six and 10 who are benefiting from an initiative launched by a Syrian teacher who lives in this 142-tent camp.

The teacher, Majid, who did not give his full name, said he noticed that several children had nothing to do in the camp.

“So I thought of bringing together as many children as possible in one place to teach them and let them do something useful during their free time,” he told The Jordan Times as he waited for the children to finish drawing.

In the beginning, Majid turned his own tent into a classroom and began approaching families to send their children.

“I held classes in my tent for five-and-a-half months. After that, a volunteer group supported me by providing a huge tent to teach students,” added Majid, who worked as a teacher in Syria for 10 years.

Students, he said, are classified into two levels in accordance with their ages.

“Classes begin at 10am and wrap up at 2pm,” Majid said, noting that he teaches students the Syrian curriculum.

He said he volunteered to teach the children, but some families pay him.

The Syrian teacher noted that many children were unable to go to the nearby schools because they could not afford the expenses of public transportation.

Fakhir Abdul Fattah said he was excited when he heard that a small school was established in the camp.

“I like to write a lot. When classes finish, I go back to our family tent and write all day,” the 11-year-old told The Jordan Times as he showed his teacher his notebook.

Abdul Fattah said the teacher rewards students who get full marks.

“I got a toy because I got a full mark,” he said with a smile.

Majid noted that he also organises field trips in the capital to entertain the children and encourage them to keep learning.

“Sometimes I take them to the nearby malls.”

The Syrian teacher said some families did not want to send their children to his school despite several attempts to convince them.

“They prefer to send them to work and make money rather than learn at the school,” he added, expressing hope that his students can receive more support to make the educational process in the camp more beneficial.

Sewar Sawalha, public relations director at Save the Children, said the organisation holds several campaigns at refugee camps and host communities to raise Syrians’ awareness on the importance of education.

“We try to help Syrian children in coordination with UNICEF and the Ministry of Education to enrol them in local schools,” Sawalha said in a phone interview, adding that many public schools have resorted to the double-shift system to accommodate the great number of students.

She said they distribute UNICEF schoolbags, which include textbooks and stationery, to Syrian refugees, adding that they will contact Majid and look into the best way to support the children at the makeshift camp.

For Abdul Fattah, Majid has been a role model.

“I want to follow in my teacher’s footsteps and become a successful educator. When I grow up, I want to help children learn.”