You are here

Leaving marks on the mind

By Sally Bland - May 24,2015 - Last updated at May 24,2015

A List to Remember

Janset Berkok Shami

Amman, 2015

Pp. 189

The thirteen stories in this collection attest to the powerful tools of observation possessed by the author, Janset Shami. With half the stories set in Turkey and half in Jordan, she writes of the world we know, yet reveals layers of human experience to which not all of us are attune. Her perceptive descriptions apply both to her characters’ mental states and the material world, whether nature or built environments. The fact that most of the stories are told in first-person narrative only increases their impact.

“A List to Remember” takes its title from the first story which presents a mother’s micro-managing of her daughter’s life. Most of the story consists of lists — the long one the mother makes specifying in detail how her daughter shall spend her day, and shorter ones reflecting her daughter’s reaction. The last list shows that such domineering has left indelible marks on the daughter’s psyche, a theme that recurs in different guises in other stories, illustrating the detrimental results of boxing people in and denying their dreams.

Unique, often idiosyncratic, characters appear in all the stories, as do exceptional situations. There are ill-fated love affairs, physical and psychological abuse, honour crimes, cultural dissonance and children confronted with outrageous adult behaviour which they can hardly understand but must bear the consequences of. Dramatic events are related in an understated way, sustaining focus on the characters’ emotional responses.

Most of the stories involve family relations. In Shami’s rendition, life is no fairy tale. Not one story has a neatly pencilled happy ending, though a few intimate future hope. As the narrator of one story confides, “Love is a frightening pantomime whichever way one looks at it. It becomes more frightening when marriage turns it into a full-length play.” (p. 57)

In the Turkish stories, the roots of family dysfunction are personal, arising from certain characters’ psychological make-up or, occasionally, poverty-driven.

In the Jordanian stories, by contrast, problematic situations are most often connected to external causes, such as war and displacement. Palestine looms large in these stories, such as the one told by a young man about his band playing for refugee camp weddings, who says: “We are one happy, unhappy, noisy family trying to forget tomorrow as we wait for miracles.” (p. 94)

More ominous is the story about a freedom fighter who abuses his son due to his frustration at not being able to write a book that will guide the Palestinians to victory. As in the other stories, Shami doesn’t pass judgement; the plot speaks for itself via his wife’s ambiguity towards the medals he received for heroism.

Reflecting the diversity of interpersonal relations, some stories show that friendships can be as important as family. Several feature women who derive little satisfaction from their marriage, instead investing their emotions in the lives and loves of women friends. Still others show groups and small communities drawn together by common interests or shared dilemmas. Many stories gain added complexity when Shami weaves cultural references and pursuits, such as music, theatre, film or art, into the plot.

Original images abound. A devious woman’s conscience is described as “a feeble old thing, kind of a bee, which occasionally forgot to buzz”. (p. 51)

A woman faced with her mother’s interference to the point of breaking up her family is seen as follows: “Inhaling her mother’s convictions and letting them out with little or no interpretation had turned Nesrin into a pair of bellows.” (p. 148)

Even inanimate objects take on a life of their own by virtue of Shami’s skilful pen. Subtle details in dress, dwellings and habits depict the gap between rich and poor, and different cultures.

An introduction by Professor Emerita of the University of Texas Eileen Lundy, who joined the author’s writing group while she lived in Amman, provides interesting biographical information about Shami to address the question of how she comes up with her intriguing characters and situations.

In the preface, Shami expresses hope that her stories “will leave some marks on your minds”, elaborating on the theme of the story, “Wheels on the Cardo”, which features still perceptible grooves left by chariots in Jerash’s Roman street. To Shami, this signifies that “no life will be ignored by history or God”. (p. 13)

Since her stories are so complex and open-ended, it is impossible to predict all the “marks” they will leave on readers. Yet, although there is no moralising, the thoughtful reader will most probably ponder how humans should treat each other, and especially children.

“A List to Remember” can be found at the University Bookshop.

Related Articles

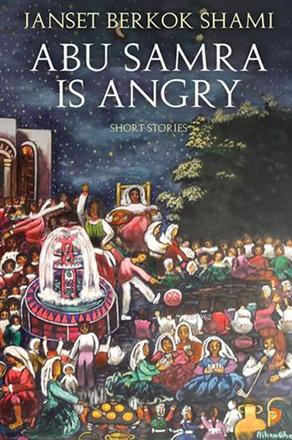

Abu Samra Is Angry: Short StoriesJanset Berkok ShamiIstanbul: Cinius Yayinlari, 2018Pp.

Fahrelnissa and I: A MemoirJanset Berkok ShamiIstanbul: Cinius Publishing House, 2016Pp.

In her short story collection "A List to Remember", Turkish Amman resident Janset Berkok Shami illustrates the personal repercussions of the political and social upheavals to which people in this area have been subjected.