AMMAN — Much has changed in archaeology since fictional hero Indiana Jones fought the Nazis in Cairo with bullwhip in hand in his quest for the Ark of the Covenant, the chest containing the tablets of stone inscribed with the Ten Commandments.

Technologies such as 3D imaging, geographic information system (GIS) and airborne laser mapping are used alongside trowels and shovels by today's archaeologists who hung up their whips a long time ago.

Combining commercial gadgets like GPS, laptops and smartphones with devices borrowed from biology, chemistry, physics and engineering, scientists today are equipped with a cutting edge toolkit, snatching unprecedented glimpses from lost civilisations.

“Archaeology is a process, but from Indiana Jones movies you would take away that it is just about going somewhere and grabbing artefacts," American scientist Glenn Corbett told The Jordan Times, adding the film franchise starring Harrison Ford got him “hooked on this profession”.

The 36-year-old archaeologist from North Carolina implemented pioneering computer technology to break down some 2,000-year-old epigraphies found in the “towering, wind-swept landscape of southern Jordan”.

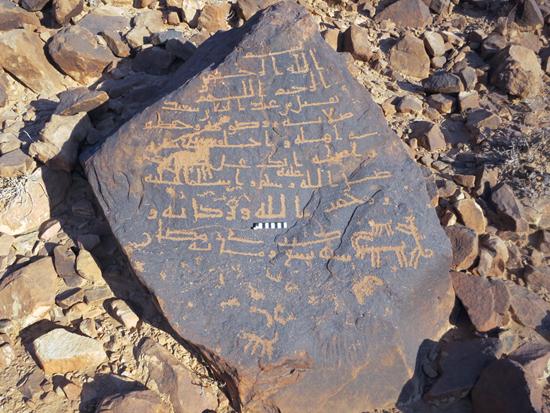

Focusing on the archaeological remains of pre-Islamic Arabia, Corbett, together with the American Centre of Oriental Research, has been recording around 1,800 inscriptions on over 1,000 boulders and rock faces along the Wadi Hafir, a very narrow valley within Wadi Rum, some 300km south of Amman, using photographs and GPS coordinates since 2005.

“My approach to these inscriptions and drawings has been something unique since I focused on where the inscriptions were found, differing from the past when people would only know that they found a lot of inscriptions in a certain area but they wouldn’t necessarily map them within their landscape," he said.

Corbett added that mapping an archaeological location helps identify patterns and tells a little bit more about who the residents were, how were they using the landscape and why they may have been carving these particular messages.

He surveyed the valley's different parts using GPS coordinates to locate as many stones and inscriptions as he could.

"I would then take these GPS points and put them into a GIS — a system designed to capture, store, manipulate, analyse and present all types of geographical data — trying to find exactly where they were found," Corbett said.

"By analysing patterns within the GIS, especially the way that the winter rains drained through this long valley, I was able to determine that inscription clusters concentrated in very specific places where the most amount of water would flow during the winter where the nomads could water their herds and hunt animals," he added.

"I became increasingly interested over my career by the impact that the ancient Arabian tribes of the Arabian Peninsula had on the economy, religion, cultures of the broader Near Eastern peoples, of the Biblical people."

These inscriptions are the primary means of understanding and documenting the cultural world of the tribes who traded in incense from south Arabia to the Mediterranean (around 1,600km) for a period of almost 1,500 years.

This incense trade presumably started about 1,000BC to only fade out — as far as archaeologists can determine — in around the 4th century AD.

Incense was sought for religious, medicinal and especially personal use in a time before daily baths.

It was the importance of this trade that gave rise to powerful kingdoms like the Nabataeans between the late 4th century BC and the 1st century AD, according to historians.

Inscriptions

The inscriptions lack enough linguistic information to show precisely what language they belong to. However, based on Corbett’s studies, they were languages and dialects akin to — though not identical to — classical Arabic “as they were written in an alphabetical set ranging between 26 and 28 characters".

"The particular dialect we find in southern Jordan has become known as Hismaic, since the Wadi Ram desert was called the Hisma," Corbett said, adding that the inscriptions may date back to the time of the Nabataeans.

With the vast majority of the inscriptions simply reading names like, "I am Abdullah son of Said" and including names of ancestors, it is possible to trace up to six levels of genealogy, the archaeologist said, adding that so-called love and emotional texts were part of his "loot".

"The most common type seems to express some sense of love and longing for someone who is not there... sometimes they would write the name of the other person or just leave it open-ended."

A big part of the drawings found in Wadi Hafir depict camels — the majority of them females — in almost an iconographic way, either by themselves or with a rider.

A camel is identified in drawings as female if its tail is upturned, according to Corbett.

"Depicting camels might have been a sign of property and wealth;" however, according to Corbett’s studies, there is some evidence that the female camel was seen as a medium, a symbolic vehicle by which people understood the passage between this world and the other, since "camels were also buried along their owners when they passed away."

Photography

George Bevan, a professor of classics at Canada's Queens University Ontario with an interest in computer science and digital photography, approached Corbett two years ago after hearing about his work.

Trying to apply advanced digital photography techniques to better understand ancient inscriptions, Bevan teamed up with Corbett for a 10-day trial season in Wadi Hafir in 2012, using new digital photographic methods for the recording and analysis of the faded inscriptions.

"We reached those areas following my GPS points, and photographed these stones with the technique George developed, and once these images were analysed via computer programmes, we found we had great success in better reading and interpretation," Corbett said.

"It did look like magic."

Employing digital photogrammetry to study the inscriptions, Bevan and Corbett used the geometry of the position of the camera relative to the position of the photographed stone and the angle of the photographs to triangulate a single point of the object in three dimensions, taking up to 2,000 pictures of the same object while making sure the images overlap as much as possible.

"You get sort of [a] 'photo-mosaic' of the entire surface of the stone whose shared points produce dynamic three-dimensional representations of carved surfaces, informative relighting and enhancement of worn carvings, and super high-resolution images once on a computer, all of which open up new vistas for the analysis, interpretation, and presentation of epigraphic and rock art."

Through this method, Corbett said he could see something that he missed in previous observations, like a random figure of a man with a dagger riding a camel — which was there but could not be seen with the naked eye — thus making technology the new and ultimate "archaeologists’ whip".