You are here

Photo archive provides rare insight into Wadi Rum treasures

By Saeb Rawashdeh - Dec 16,2017 - Last updated at Dec 16,2017

AMMAN — William Jobling, the late professor at the University of Sydney, was the head of the Aqaba-Maan Archaeological and Epigraphic Survey (AMAES) conducted between 1980 and 1990, which documented the archaeological heritage and natural landscape of Jordan’s Hisma Desert (better known as Wadi Rum).

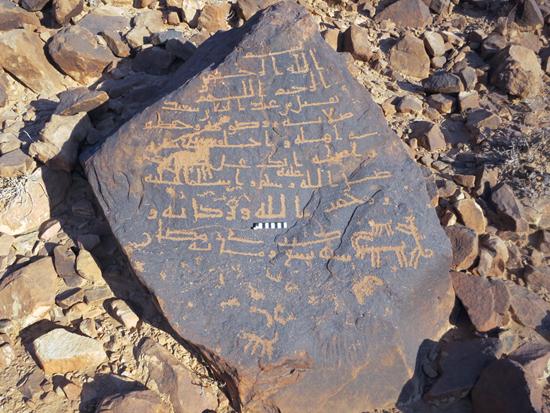

In nine field seasons, the AMAES produced photographic documentation, maps, and drawings of the desert landscape’s little known archaeology, particularly thousands of Thamudic inscriptions and rock drawings dated to more than 2,000 years ago.

After his sudden death in 1994, Jobling’s impressive archive passed first to his longtime field assistant and photographer Richard Morgan and then, more recently in 2016, to the American Centre of Oriental Research (ACOR) in Amman.

At ACOR, the archive is now being catalogued, digitised and made available to scholars interested in Wadi Rum’s ancient past. The initial aim is to scan and make available more than 5,000 colour slides photographed during the survey, according to Glenn Corbett, ACOR’s grants officer and former associate director.

Corbett, who received his PhD in 2010 from the University of Chicago, has been working in Jordan for several decades, particularly in Wadi Hafir, an area of Wadi Rum where the Jobling survey recorded thousands of ancient inscriptions.

“[The Jobling] collection is now housed here at ACOR and we, with the help and support of the University of Sydney and the Near Eastern Archaeology Foundation, are beginning to preserve this very important primary data about Wadi Rum,” Corbett said in a recent interview for The Jordan Times.

“A lot of people go to Wadi Rum, they see the amazing scenery, the majestic mountains, the colourful sand dunes, the ancient springs, and they appreciate the nature of the place, but often they don’t know that there is an incredible, immense amount of archaeology to be seen,” noted the American scholar, adding that while there are a handful of traditional archaeological sites, what distinguishes Wadi Rum are the thousands of ancient inscriptions and drawings found carved in its mountains and rock faces.

The AMAES was the first systematic archaeological exploration and survey of Wadi Rum, Corbett highlighted, adding that over the course the decade-long project, Jobling and his team recorded thousands of Thamudic, Nabataean, Greek, Latin and Kufic inscriptions.

“The survey’s findings really provided tremendous insight into the way that people lived for several thousand years in what we now perceive to be a remote desert region,” said Corbett.

The AMAES covered a vast region, covering more than 2,500 square kilometres between Maan, Aqaba, and the Saudi border post of Mudawwara, although Wadi Rum was the survey’s focus, he explained.

“In addition to inscriptions, the survey identified archaeological sites characteristic of Jordan’s deserts. If you go to Wadi Rum, for example, you’ll see lot of Nabataean dams, water channels, and cisterns carved into the rock faces and springs,” Corbett noted.

Furthermore, the survey found many examples of prehistoric rock art predating, perhaps by several thousand years, the Thamudic carvings.

“It was during the course of my research that I came across the work of William Jobling and I was given access to the archives that were in Australia. I was able to use the information Jobling collected to inform my own field research in Wadi Hafir,” Corbett explained.

After completing his PhD, Corbett was committed to making sure the entirety of the Jobling archive would be made available to researchers.

In September 2016, he travelled to Australia and shipped 20 boxes of archival material to Amman, where the ACOR team is now digitising all of the survey’s photos, drawings, and notes, he said.

“We shouldn’t forget that Wadi Rum, an area we often consider remote and desolate, is actually changing quite rapidly,” Corbett emphasised.

“It’s important to keep in mind that more tourists and more businesses in Wadi Rum are also negatively affecting its archaeology, so it’s important that we preserve documentation of what these places looked like before they change further,” Corbett concluded.

Related Articles

AMMAN — Two scholars from the American Centre of Oriental Research (ACOR), Glenn Corbett and Firas Bqain, have spent years studying an often

Much has changed in archaeology since fictional hero Indiana Jones fought the Nazis in Cairo with bullwhip in hand in his quest for the Ark of the Covenant, the chest containing the tablets of stone inscribed with the Ten Commandments.

AMMAN – The late Australian scholar from The University of Sydney, William Jobling, meticulously studied inscriptions in the Wadi Rum back i