You are here

Globalisation under the spotlight at Davos

By AFP - May 24,2022 - Last updated at May 24,2022

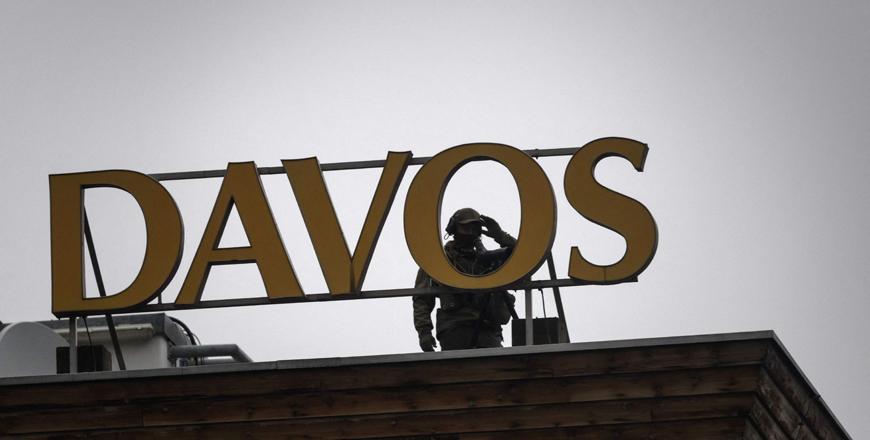

A special police officer is seen on the roof of the Congress hotel during a session at the World Economic Forum annual meeting in Davos on Tuesday (AFP photo)

DAVOS, Switzerland — The question of whether the coronavirus pandemic and the war in Ukraine have sounded the death knell for globalisation has dominated the World Economic Forum (WEF) in Swiss resort Davos.

Some believe the crises have unleashed an opportunity for a transformation of international trade and supply chains as the world economy slows down.

Once advocated by anti-globalisation movements, far from the quiet rooms at Davos, talk of "deglobalisation" is back in the face of supply chain disruptions linked to the Ukraine conflict and lockdowns in China.

In the hope of building stronger networks unaffected by crises like war, deglobalisation would mean bringing production back closer to home, thus allowing the movement of goods across shorter distances.

The issue has become acute after COVID-19 and the misery at Shanghai port.

The Chinese city has become a symbol of global supply chain woes after its factories were closed for weeks and containers piled up as China sticks stubbornly to a zero-COVID strategy, causing delivery delays worldwide.

Since Russia's invasion of Ukraine, global food prices have hit an all-time high as the two countries make up a huge share of the globe's exports in several major commodities, like wheat.

Such snags are leading many, including the world's biggest companies, to consider what production should look like in the future.

Globalisation is "temporarily pausing", Loic Tassel, president for Europe at the consumer goods giant Procter & Gamble said during an event at Davos.

"The price to pay or the time to wait is not compatible anymore with our industry," Tassel said, giving the example of Shanghai, which is the world's busiest container port.

"We are now bringing into the equation the cost and resilience of the supply chain, it was not in our mind three years ago," he said.

But rather than talk about "deglobalisation", Pamela Coke-Hamilton, director of the Geneva-based agency International Trade Centre, preferred to speak about diversification and relocalisation — where supply chains are closer and in areas where conflict is far away.

"The change will come by the shifting to near sourcing value chains," she said.

Sceptics said companies sought the cheapest options despite being aware of the risk of huge dependence on certain regions.

"We never imported so much from China as when we said we should rely on it less," noted Gilles Moec, chief economist at French insurance giant Axa, on the sidelines of Davos.

"One of the reasons why people are so nervous right now is that if China was unable to meet global demand because of the pandemic, that would be a catastrophe," he added.

Globalisation's identity crisis comes at a time when pessimism reigns over the future of the global economy.

"The horizon has darkened," said International Monetary Fund head Kristalina Georgieva at Davos on Monday.

While a global growth forecast of 3.6 per cent excludes the risk of recession right now, "it doesn't mean it is out of question" for certain countries.

The clouds are already gathering in developed countries, according to data from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).

There was only 0.1 per cent growth in the first quarter of 2022, the OECD said Monday, and gross domestic product even fell by 0.1 per cent among G-7 countries.

The second quarter is likely to be equally sluggish, as the adverse effects of the Ukraine war and China's lockdowns take root.

After governments spent copiously during the pandemic, "the response to put in place is not obvious and that worries everyone a little," Axa's Moec said.

Meanwhile, inflation is pushing central banks, including the US Federal Reserve, to raise interest rates, which will make it costlier for both companies and consumers to borrow and slow economic activity.

The European Central Bank signalled on Monday the end of negative rates despite the European Commission's growth forecast for 2022 last week for the eurozone, from four per cent to 2.7 per cent.

Figures from China, the global engine of growth, revealed the pain inflicted by Beijing's strict zero-COVID policy as retail sales and factory production slumped to their lowest in over two years, while unemployment is near record levels.

Related Articles

DAVOS — Chinese Premier Li Qiang said on Tuesday the country's economy was expected to have grown by around 5.2 per cent in 2023, as he addr

LONDON — Stock markets mostly slid and other major assets including the dollar and oil weakened Thursday after disappointing US data renewed

LONDON — Europe's natural gas price on Friday sank under 50 euros for the first time in nearly a year and a half, as a mild winter curbs hea