You are here

‘Disguised hidden wounds’

By Sally Bland - Nov 28,2021 - Last updated at Nov 28,2021

Paradise

Abdulrazak Gurnah

New York: The New Press, 1994

Pp. 246

It is roughly a decade since the Nobel Prize in Literature ventured out of the global North. Even then, this year’s recipient, Abdulrazak Gurnah, resides in the UK, but he was born in Zanzibar, now part of Tanzania. His ancestry is Arab, his first language, Swahili, and his writing reflects this diverse background.

Due to ancient trade routes, the eastern coast of Africa and adjacent islands, such as Zanzibar, are very diverse demographically, linguistically, culturally and in terms of religion. Accordingly, Gurnah’s novel, “Paradise”, is peopled with urban, rural and tribal Africans, characters of Arab and Indian origin. There are Muslims, Hindus, Sikhs, Christians and animists; speakers of Arabic and dialects of Swahili. How this diversity plays out is one element that makes the novel fascinating and a bit exotic for those of us who know little about this region.

Gurnah, however, nips any exotic or romanticised interpretations in the bud with his realistic and often harsh portrayal and irony, starting with the title of the novel. Though the concept of paradise may represent people’s aspirations for freedom, dignity and a moderately comfortable life, very few of them find themselves in a heavenly situation. Nor are there any indications that they have much choice, or that their lot in life will improve. Even the wealthy and successful, like the prominent merchant, Aziz, will find their days numbered as German and British imperial forces begin penetrating the area, and war brews between them. From the first pages, Gurnah calls attention to the looming colonial presence, but it is not till the last page that one grasps the full extent of it.

Parallel to describing the conditions that allowed colonial penetration, “Paradise” is a coming-of-age story focusing on twelve-year-old Yusuf, who lives in Kawa, where his parents had migrated when it was a boom town because the Germans used it as a depot while building a railroad to the interior. Yusef’s parents are left poorer than ever when the boom ends, but the German presence lingers, impacting on the psyche of the locals. Yusuf likes to hang out with older boys whose parents had come from all over to work for the Germans piecemeal: “They were only ever paid for the work they did, and at times there was no work. Yusuf had heard the boys say that the Germans hanged people if they did not work hard enough”. (p. 7)

Yet, at first, oppression seems to come at least as much from local sources. Yusuf’s father gives him to the merchant Aziz in lieu of the insurmountable debt he owes him. They call him Uncle Aziz and he has visited the family before, so Yusuf is totally caught off-guard as to what is really happening: “It never occurred to him, not even for one brief moment, that he might be gone from his parents for a long time, or that he might never see them again. It never occurred to him to ask when he would be returning. He never thought to ask why he was accompanying Uncle Aziz on his journey…” (p. 17)

Yusuf’s naivete continues for a long time after arriving at Aziz’s home in a town on the coast. He is treated kindly by the master and expected to work in his shop, assisting an older boy, Khalil, who was also sold into service and tries to disabuse Yusuf of the notion that Aziz is his uncle. Though Khalil never uses the word slave, he knows “his place”. Yusuf, on the other hand, indulges in dreams and fantasies that eventually threaten his status in the household. In a sense, Aziz’s home, and especially its beautiful garden, is paradise for Yusuf.

Before things reach the breaking point, Yusuf is treated most favourably and groomed to take a bigger share in Aziz’s trading business. This entails going on long journeys into the interior where Aziz exchanges his wares for whatever the local people have to offer. It is on these journeys that Yusuf matures. He realises that his excessive good nature is “only disguised hidden wounds” as he wises up to Aziz’s game: “He cuts you in above your means, and then when you can’t pay up he takes everything… takes their sons and daughters. This is like the days of slavery”. (pp. 175, 88-89)

From these journeys, Yusuf also gains a sense of the precariousness of human existence. The pure physical labour demanded of the porters is astounding, and the caravan often comes under vicious attack by the locals. “Everywhere they went now they found the Europeans had got there before them, and had installed soldiers and officials telling the people that they had come to save them from the enemies who only sought to make slaves of them… The first thing they build is a lock-up, then a church, then a market-shed so that they can keep the trade under their eyes and then tax it”. (p. 72)

Gurnah’s writing is elegant even when describing the most horrible scenes. He has a special gift for storytelling, and besides the main plot, there are many stories within stories that convey legends, myths and real local history, while dreams and fantasies poignantly reveal the characters’ feelings, especially Yusuf’s. Simple daily past times and conversations are written in a way that reveals much about society. In short, Gurnah is a highly skilled writer who tells the reader much about social conditions and personal emotions without seeming to pontificate. “Paradise” was short-listed for the 1994 Booker Prize and is often mentioned as a reason for Gurnah receiving the Nobel Prize. Reading it whets the appetite for reading other of his novels.

Related Articles

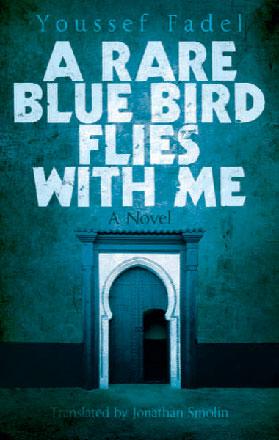

A Rare Blue Bird Flies with MeYoussef FadelTranslated by Jonathan SmolinCairo-New York: Hoopoe/American University in Cairo Press, 2016Pp.

AMMAN — The government has approved a request by the family of Iraq’s former foreign minister Tariq Aziz, who died in Iraq on Friday, to bur

AMMAN — Former Iraqi foreign minister Tariq Aziz was buried in Madaba city, southwest of the capital, on Saturday. The body of Aziz arr