You are here

‘Magical realism between East and West’

By Sally Bland - Dec 15,2019 - Last updated at Dec 15,2019

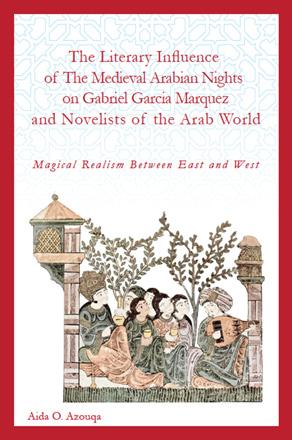

The Literary Influence of the Mediaeval Arabian Nights on Gabriel Garcia Marquez and Novelists of the Arab World

Aida O. Azouqa

US-UK: The Edwin Mellen Press, 2019

Pp. 210

It is truly a delight to have some of one’s favourite authors brought together in the perceptive analysis of Aida Azouqa, the late professor of English and Comparative Literature at the University of Jordan. As Muhsin Jasim Al Musawi of Columbia University writes in the Foreword, “Not much has been written on magical realism in Arabic narrative… Azouqa’s is an important exploration into the modern Arabic novel, its marvellous realistic turn, that received only a little and passing attention before.” (pp. iii, v)

While much has been written about “The Thousand and One Nights” (hereafter “Arabian Nights”), this is the first book to comprehensively examine its influence on these particular authors. The book is an important contribution to comparative literature and makes a surprising connection between the “Arabian Nights” and modern science fiction. Azouqa writes that it “was inspired by the impact of the Arabian Nights on world literature. It investigates the adaptations of the Arabian Nights’ tales, its formal, thematic, and magical features” on select examples of modern literature”. (p. i)

In successive chapters, Azouqa documents the influence of the “Arabian Nights” on Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s “One Hundred Years of Solitude”, Gamal Al Ghitani’s “The Zafarani Files”, Tahar Ben Jelloun’s “The Sand Child”, Fadhil Al Azzawi’s “The Last of the Angels”, Ibrahim Al Koni’s “The Bleeding of the Stone”, and Mahmod Al Wardani’s “Heads Ripe for Plucking”. In addition, short but informative appendixes trace a similar influence on Naguib Mahfouz’s “Arabian Nights and Days” and Salman Rushdie’s “Midnight Children”.

Whereas magical realism originated as an art movement expressing the sense of instability in post-World War I Germany, Azouqa links its spread as a literary movement in the post-colonial world, first of all Latin America, to rejection of “the colonisers’ paradigms of otherness and dominance”, instead seeking to rediscover an authentic identity, unclouded by racist presuppositions. “Magical realism’s appeal to post-colonial societies was also the outcome of its penchant for re-establishing contact with oral traditions… the collective memories that allowed indigenous populations to re-assert their identity.” (p. 4-5)

In the case of the Arab novels which Azouqa analyses, the use of myth, legend and other “unreal” elements provided a vehicle for overturning colonial narrative as well as expressing opposition to dictatorial regimes and reinterpreting history, meanwhile allowing the authors to avoid censorship and persecution.

Most of the writers in question have acknowledged their debt to the “Arabian Nights”, and Azouqa points out the specific features which their novels share with the mediaeval text. Among these is incorporating instances of the marvellous, i.e., events which can only be explained by magic. Drawing on the work of literary theorist Tsvetan Todourov, Azouqa divides the marvellous as found in the “Arabian Nights” into three categories: hyperbolic marvellous in which the text exaggerates the details, the exotic marvellous which records larger supernatural events, and the instrumental marvellous, where “one finds gadgets, technological developments unrealised in the period described but, after all, quite possible” — the forerunner of science fiction. (p. xx)

In all these texts, the fantastic, the marvellous, the supernatural is narrated as if it is perfectly natural, thus juggling the readers’ sense of time and place, and opening up for reinterpretation of conventional history. Another major device that reconfigures the presentation of reality is the use of fragmentary oral storytelling techniques. Azouqa finds that all these novels emulate the formal attributes of the “Arabian Nights” by having frame narratives, paralleling Scheherazade’s storytelling aimed at saving her life from the tyrannical Shahrayar, “which lead to embedded stories through multiple narrators, and the use of repetitions”. (p. 157)

Azouqa cites innumerable examples of how these devices are used in the selected novels and shows their analogy to specific stories in the “Arabian Nights”. Garcia Marquez depicts a plague of insomnia that causes a whole tribe to lose their memory as a metaphor for Spanish colonialism’s destruction of Native American culture. Using the phenomenon of metamorphosis found in the “Arabian Nights”, Al Koni has his protagonist metamorphise into a waddan (a desert ram revered by his people, the Tuareq) to escape conscription into the Italian army, symbolising a return to nature and the authentic “primitive” to confront the oppressor. “Ben Jelloun uses human freaks to illustrate hybridity and Otherness in the colonial context. He based the novel’s human freaks on correspondences in the ‘Arabian Nights’.” (p. 94)

Al Wardani’s novel is narrated by three decapitated heads signifying the cruel methods employed to stamp out political opposition. Azouqa names these speaking heads as the most significant resemblance to the tales of the “Arabian Nights” which “have numerous instances of robot-like beings that scholars refer to as automatons [creatures neither living nor dead]”. (p. 145)

These are only a few of the multiple examples mustered by Azouqa to prove her thesis about the major impact of the “Arabian Nights”. In an obviously well-researched book, she moreover gives the reader an idea of the plots, themes and motivations of the selected writers. Besides having great literary value, this book shows the vast potential of literature to speak out against injustice in all its forms and to give voice to people who have been silenced by colonialism and/or modern tyranny.

Related Articles

The Palestinian Novel: From 1948 to the PresentBashir Abu-MannehUK: Cambridge University Press, 2018Pp.

At the Edge of the NightFriedo LampeTranslated from the German by Simon BeattieLondon: Hesperus Press, 2019Pp.

About My MotherTahar Ben JellounTranslated by Ros Schwartz and Lulu NormanLondon: Telegram, 2016Pp.

Opinion

Apr 09, 2025

Apr 08, 2025

- Popular

- Rated

- Commented

Apr 08, 2025

Apr 09, 2025

Newsletter

Get top stories and blog posts emailed to you each day.