You are here

‘An art that lives’

By Sally Bland - Mar 23,2014 - Last updated at Mar 23,2014

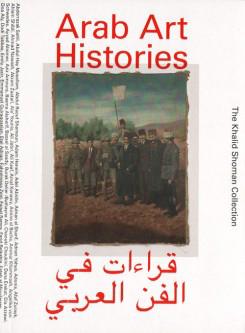

Arab Art Histories—The Khalid Shoman Collection

Edited by Sarah A. Rogers and Eline van der Vlist

Amman: The Khalid Shoman Foundation, 2013, 463 pp

Like both Darat Al Funun and the Khalid Shoman Collection which it covers, this book is firmly grounded in Amman, but at the same time indicative of a regional cultural network with international outreach. Comprising eight major essays, scores of personal reflections and hundreds of images, it tells the story of how the initial efforts of Suha and Khalid Shoman to support local artists, by buying their works, grew into a broadly based institution perched on the cutting edge of contemporary Arab art. In human terms, this story shows that individuals can make a difference if they join forces with others in the pursuit of beauty, excellence and enlightenment.

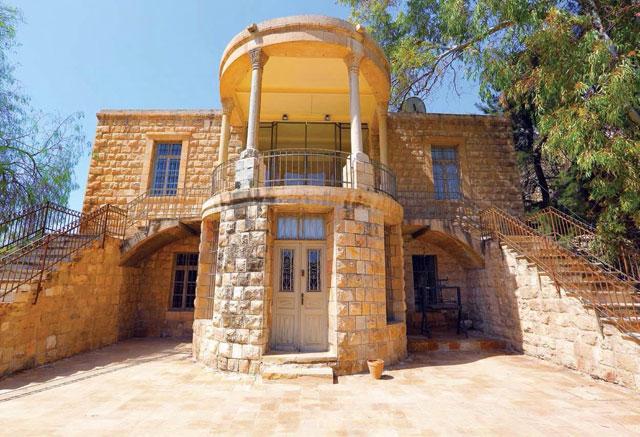

Editor Sarah Rodgers traces the history of Darat back to Suha Shoman's working relationship with Fahrelnissa, Shaker Hassan, Ali Jabri, Ammar Khammash and many others, and how she realised that what artists needed was not a gallery, "but a home that provided opportunities for research, creativity, and exchange". (p. 27) In Suha Shoman's words, "Arab artists assimilated tradition and modernity, experimented in all medias, and revisited their history." Eventually they created "an art that goes beyond labels or stereotyped definitions. An art that lives". (p. 61)

The most delightful reading in the book is the reflections of some of the many artists who have benefitted from and contributed to Darat and the collection. Each offers a unique definition of the institution, mirroring its openness, value and multiple functions. For Emily Jacir, Darat has been "a regular site of pilgrimage" as she transited between Palestine and elsewhere, offering "an education and exposure to works, writers, and ideas". (p. 63) Mohammad Al Asad posits Darat's creation as an "initial step towards rediscovering and re-establishing the importance of Amman's core". (p. 116) Nada Shabout calls it a "blissful oasis" which provided unparalleled research possibilities back in pre-Internet days when there were few resources on Arab art. Sheena Wagstaff tells how she and Suha Shoman "explored the dream of establishing a programme that would build mutual trust via an open negotiation of respective cultural histories, and most crucially, the identification of shared values", leading to a joint exhibition that travelled between London's Tate Gallery and Darat. (p. 172)

Sama Alshaibi can't decide how to capture Darat's essence—"support network; forum; educational space; gallery; place to hang out; stage for performance; artist colony; publisher; art collection; production venue; and studio" — finally settling on "my second family". (p. 226) To Najwa Bint Ali, it was "a haven for Iraqi artists… a community of inspiring people". (p. 230) Samia Halabi praises Darat's "uncompromising insistence on quality". (p. 232) Wijdan F. Al Hashemi views Darat as complementary to the Jordan National Gallery, while Pierre Bikai recalls the excavation of the archaeological treasures found in its garden. Tania Tamari Nasir calls Darat an "exquisite venue for celebrating the arts". (p. 284) To Mamdouh Bisharat, it is "a jewel… a private institution with a public spirit". (p. 286) There are many other reflections in English and Arabic.

The essays are more challenging to read not so much because of their theoretical tone, as for the unconventional ideas they propose. In the open-ended spirit of Darat and the collection, the essayists eschew preconceived notions about art history to tell the stories of select artists and pieces in a sociopolitical context. Faisel Darraj focuses on why the "Arab modernity project was in crisis from the outset," while chronicling the role of Arab modernists in the arts. (p. 81) Anneka Lenssen discusses art in relation to its audience, as evidenced in the setting of the café. Kirsten Scheid writes about the Arab body in art — not nude paintings, but how "the vulnerability of the Arab body to international politics" is represented. (p. 252) Saleem Al-Bahloly addresses "how the handling of light, space and frame [in photographs] works to produce intelligible form for some of the problems that have characterised the twentieth century in the Middle East". (p. 255) Ulrich Loock discusses what it means that the "Shomans have built the collection up through their continuous involvement in and with the moments of a present that evinces constant change, rather than from a historical distance." (p. 305) Stephen Sheehi writes about Nicola Saig, "Jerusalem's First Painter", who transitioned from iconography to modern painting. Hassan Khan trains a critical eye on all modern Arab art.

What remains unstated in this review is the pure pleasure of viewing the art works reproduced in the book. Due to obvious space limitations, some of the images are too small to fully appreciate, but this can be solved by visiting Darat Al Funun's 25th anniversary exhibition, which runs until April 30. "Arab Art Histories" is available at Darat Al Funun or can be ordered at www.ideabooks.nl

Sally Bland

Related Articles

AMMAN — Darat Al Funun-The Khalid Shoman Foundation recently received the Jerusalem Award for Culture and Creativity in the Arab world, in r

AMMAN — As soon as Jehad Ameri graduated from school 22 years ago, he began looking for a centre to further enhance his artistic skills.&nbs

Her Majesty Queen Rania on Monday visited Darat Al Funun, marking the 25th anniversary of its establishment as a home for the arts and artists of Jordan and the Arab world.