You are here

‘Freeing people’s minds and tongues’

By Sally Bland - Apr 10,2016 - Last updated at Apr 10,2016

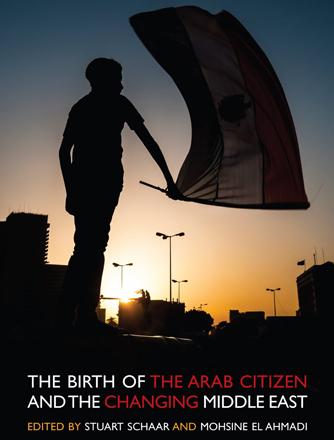

The Birth of the Arab Citizen and the Changing Middle East

Edited by Stuart Schaar and Mohsine El Ahmadi

US: Olive Branch Press/Interlink Publishing, 2016

Pp. 326

Instead of wasting time bewailing the dismal results of the Arab uprisings so far, this book focuses on actual changes that could portend a better future. Editor Stuart Schaar argues persuasively for taking “a long view approach”. While democracy and social justice remain elusive, “social movements in the region have benefited from the revolts, not only by freeing people’s minds and tongues, but also by demonstrating the advantages of collective action”. (pp. 7-8)

The other twenty-one contributing writers, mainly academics, would seem to concur, focusing on the human capacities that were unleashed and enhanced in different countries and fields, from street politics to culture.

Mouin Rabbani leads off with “The Un-Islamic State,” asserting that “ISIS represents a thoroughly modern project and… explanations for its existence are primarily to be found in the political landscape in which it operates rather than Islamic ideology”. Registering doubt that it can be defeated by Western military intervention, he concludes: “Only the emergence of institutions enjoying sufficient popular — and not necessarily electoral — legitimacy can address deep-seated grievances and peacefully resolve the conflicts that allow movements such as ISIS to thrive, and thereby reassert governance...” (pp. 19, 24)

The issue of how to institutionalise the changes people demanded was the rock on which most uprisings floundered. While many articles attest to the birth of a new, more active and fearless Arab citizen, they also show how mass participation was soon curtailed. As Omar Foda writes on Egypt, “Although some have argued that this revolt was unique because it was documented tweet-by-tweet, its true uniqueness lies in the multitude of narratives that it produced.” (p. 43)

Yet, many of the newly emergent voices were excluded as the politics of rebuilding the country took hold.

Sahar Khamis, however, notes that it’s not only about politics; other dynamics have been unleashed that can have great future impact. “Arab women’s prominent positions of leadership and activism in both the real and virtual worlds provide firm evidence that the Arab uprising has been more than just a political revolt. Rather, it has been a social and communications revolt as well, since Arab women activists have in fact been upending traditional hierarchies, reinterpreting religious dogma, breaking taboos and bringing new issues into the public sphere... The mere fact that women in some of the most traditional and conservative Arab societies — such as Libya, Yemen and Bahrain — broke out of their cocoons and rallied in huge numbers for many months under the most dangerous conditions… signals a new era in the history of this region.” (p. 156-7)

Admirably, this book does not overlook Palestine as did some media in the heat of the Arab uprisings. Abaher El-Sakka examines renewed activism among Palestinian youth in response to regional events, noting that “unlike neighbouring Arab countries, Palestinians have long voiced their views in public. But now, for the first time, they were directly challenging the Palestinian authorities”, who tried to appear neutral or sided with the regimes being deposed. (p. 88)

While the Internet and social media skills of the new Arab citizen are recognised, there is just as much, if not more, importance attached to popular activism to reclaim public space. Based on interviews with young Tunisian cyber activists “who helped prepare the way for revolt”, Stuart Schaar gives a totally fascinating profile of Sofiene Ben Haj Mohamed, Fatma Riahi and Skander Ben Hamda — all of whom gave “most credit to the Tunisians who remained on the barricades facing the police, snipers, and armed thugs day after day...” (p. 197)

Evaluating the impact of the uprisings on film, Viola Shafiq notes that the “unparallelled creative commotion” of Tahrir Square at its height was much more inclusive than the ancient Greek agora, which is often cited as a model of democracy. (p. 211)

Carol Solomon discusses the sociopolitical and creative dimensions of the street art that transformed public space in cities across Tunisia, whereas censorship had previously precluded this genre, and beautiful photos document the expressive excellence so quickly achieved. In a similar vein, Farid El Asri explores the relation between music and revolt.

While celebrating the explosion of human capacity and creativity, the book does not shy away from the problems and challenges facing the people’s quest for freedom, bread and dignity, whether emanating from the pillars of the old regimes, Islamists or Western policy.

There are chapters on the staying power of the Syrian regime, and why, despite substantial protests in some cases, there were not full-blown revolts in Algeria, Jordan, Morocco or the Gulf States. Several contributors address the economics of transition. As editor Mohsine El Ahmadi writes in the conclusion, “The path of political, social and economic renewal that lies ahead is even longer and has only just begun.” (p. 310)

Related Articles

Arab Dawn: Arab Youth and the Demographic Dividend They Will BringBessma MomaniUniversity of Toronto Press, 2015Pp.

Shifting Sands: The Unravelling of the Old Order in the Middle EastEdited by Raja Shehadeh and Penny JohnsonUS: Olive Branch Press/Interlink

Winds of Change: The Challenge of Modernity in the Middle East and North AfricaEdited by Cyrus Rohani and Behrooz SabetLondon: Saqi Books, 2