You are here

Prelude to war and colonialism

By Sally Bland - Aug 13,2018 - Last updated at Aug 13,2018

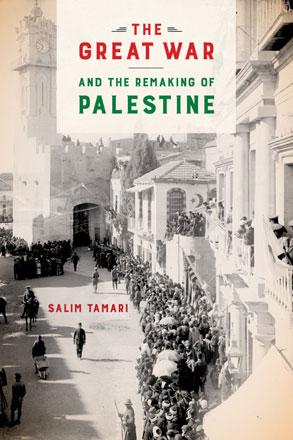

The Great War and the Remaking of Palestine

Salim Tamari

US: University of California Press, 2017

Pp. 207

The last decade of the Ottoman Empire was a time of great change, not least the 1908 constitutional revolution led by the Committee of Union and Progress (CUP), the overthrow of Sultan Abdul Hamid, his short-lived restoration in 1909, then the restoration of parliament and the outbreak of World War I.

In this book, Palestinian historian Salim Tamari examines what these tumultuous events meant for people, politics and culture in Bilad Al Sham, and how they shaped Palestine in particular. “It was during this period that the term ‘Southern Syria’ became synonymous with ‘Palestine’, but the expression gained an added political significance after 1918… in response to the British-Zionist schemes of separating Palestine from Syria.” (p. 3)

To illustrate the changes, Tamari addresses a series of topics such as urban planning, modernisation, infrastructure projects and wartime mobilisation undertaken by Istanbul, the transformation of urban pubic space, as well as developments in education and social services, and the rise of regional, nationalist and religious identities that either supported or challenged the ideology of Ottomanism.

The book is especially interesting because Tamari relies mostly on primary sources, which gives his observations authenticity and added validity. Besides old maps, newspapers, local histories and diaries, he gleans valuable facts from Ottoman-commissioned surveys of the territory and population of Beirut province, which then included Beirut, Akka, Nablus, Tripoli and Latakiyya.

Tamari’s research challenges conventional wisdom by revealing many nuances, distinctions and outright differences in how the local population reacted to these changes. For example, the constitutional revolution of 1908 was celebrated as giving more freedom by the residents of Jerusalem, Jaffa and Akka, but not Nablus, the town in Palestine most closely tied to the Ottoman Empire. To show the different perspectives, Tamari focuses on the works of two local historians from Nablus, Ihsan Al Nimr and Muhammad Izzat Darwazeh, “both eyewitnesses and participants in the political struggles of that period”. (p. 119)

Al Nimr, from a feudal family, “was a solid supporter of the Islamic salafi currents and Hamidian Ottomanism; while Darwazeh, the plebian militant, adhered briefly to the ideals of the CUP and, subsequently, moved to the Ottoman Decentralisation Party and [later] to the Freedom and Accord Party…” eventually joining the nationalist Faisali movement for the independence of Syria and Palestine. (p. 120)

Tamari finds the writing of both men useful, but credits Darwazeh with a more coherent, class-based analysis of the local conflicts in Nablus.

The book also chronicles changes wrought by the war itself, such as “major population displacements among the civilian population, which significantly affected the world of women in both rural and urban areas of Palestine”. (p. 143)

This meant fewer adult males, but many war orphans and refugees. To shed light on how these changes affected women, Tamari unearthed the notebook of Adele Shamat Azar (1886-1956) in which she describes her efforts to support and educate girl orphans and destitute women in Jaffa during the war. Oddly, her name is absent from most accounts of the early Palestinian women’s movement, because most feminist writers underestimate the importance of charitable associations. Challenging this notion, Tamari contends that her work “was a revolutionary episode in the creation of the women’s movement at the turn of the century”. (p. 141)

Tamari’s book is a valuable contribution to understanding the beginning of the 20th century in the Eastern Mediterranean, when a triangle of interests were pitted against each other and/or redefining their relationships: The Ottomans, the Arab subjects/citizens of the empire and the Allied colonial powers (Britain and France). Tamari evaluates the nature of the ties between Istanbul and the Arab provinces: Were they based on the Islamic bond as he terms it or on a concept of multicultural citizenship? Tamari also enters the debate about the nature of the CUP/Young Turks and the constitutional revolution. Did it herald more freedom, equal citizenship and modernisation or was it promoting stricter centralisation and a narrow concept of Turkification? Addressing this question, Tamari cites a report written during the war: “Muhammad Kurd Ali presented the most sophisticated case for Arab support of an Ottoman commonwealth based on Turkish-Arab unity. He also made the most succinct plea for bilingualism as an instrument of integration in the empire… Contrary to subsequent accusations by Syrian and Arab nationalists, Turkification is not posited as a forceful imposition against Arab culture. On the contrary, the report proposes a parallel process of Ottoman integration…” (p. 86)

While the outcome of World War I would seem to have made such debate irrelevant, it is still important for understanding this fateful period which ushered in the colonial division of the area and the loss of Palestine to the Zionist movement. It also provides ideas, concepts and real experience related to the meaning of citizenship and a multicultural society, lessons which could promote justice and stability in many countries of the region today.

Related Articles

AMMAN — After more than a century since the end of WWI, a sociologist has analysed the major transformations in the way people in the Middle

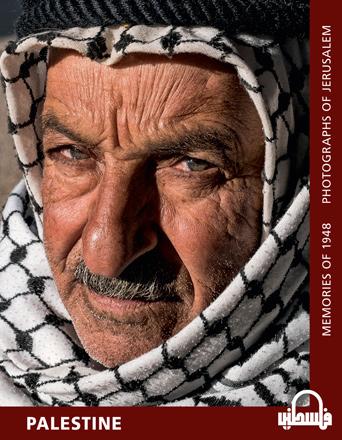

Palestine: Memories of 1948, Photographs of JerusalemChris Conti and Altair AlcantaraTranslated from French by Isabelle LavigneLondon: Hespe