You are here

Transgressing taboos with a purpose

By Sally Bland - Jul 05,2015 - Last updated at Jul 05,2015

The Bride of Amman

Fadi Zaghmout

Translated by Ruth Ahmedzai Kemp

Hong Kong: Signal 8 Press, 2015

Pp. 250

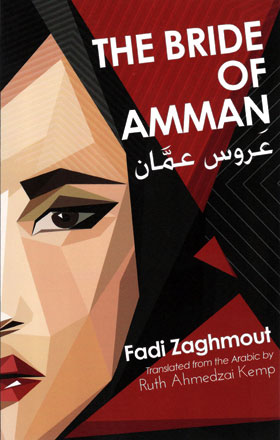

The book cover displays the cognitive dissonance and inner conflict experienced by all the major characters in “The Bride of Amman”. While the title would seem to signal happiness, the face of the woman pictured next to it is full of anxiety and pain. Marriage, and all the expectations attached to it, is just one of the societal norms which author Fadi Zaghmout problematises in his novel.

Hard-hitting prose quickly draws the reader into the lives of four young women and a man living in today’s Amman. They are close friends and share many things, not least, the risk of total devastation if they do not abide by the rules. Some refuse to be boxed in by social norms and consciously make defiant choices, while others are unwittingly set on a collision course with family and society through no fault of their own. All are seeking love and respect. They start off as irrepressible romantics, but events carve hard, cynical edges on their souls, as they discover that it is hard to remain true to their values and dreams amidst pervasive social pressure to conform.

Leila’s happiness at obtaining her degree is marred when she finds that this is not enough for her parents, relatives and neighbours, who consider it only a prelude to marriage. It is not that she rejects the idea of marriage, but she had hoped for more recognition of her academic achievement.

Salma, Leila’s older sister, suffers from remaining single, and is deeply wounded upon hearing her grandmother describe her as “an unplucked fruit left to rot”, as she nears her thirtieth birthday — her “expiry date”. (p. 22)

The story shows that judging women only by their marriageability can have catastrophic consequences.

Hayat loses her job when someone reports on her relationship with a married man, leaving her feeling vulnerable and terrified at the loss of social respect and of income she needs to finish university and contribute to her family’s upkeep. Her vulnerability is amplified by her father’s sexual abuse, which colours her self-esteem and relationships.

Rana has a more analytical view of society than her friends: “I’m rebellious by nature… very conscious of the contradictory messages I get from the world around me. Everyone seems to want to construct my moral framework for me, in a society that strikes me as schizophrenic and very masculine. Whereas I’m a female, a young woman trying to feed a craving for gender equality and personal freedom.” (p. 38)

But her awareness doesn’t protect her entirely from the dilemmas she faces after falling in love with a Muslim — a love she must keep secret from her conservative Christian family.

Ali is also under a lot of pressure to get married. In fact, he does want a family, but his preference for his own sex means that a traditional marriage would be living a lie.

By letting his characters tell their stories, Zaghmout delivers a radical critique of society from a feminist/outsider perspective, producing one of few books written by men that convincingly convey the women’s angle. Michael Cunningham’s “The Hours”, Amitov Ghosh’s “Sea of Poppies” and Arthur Golden’s “Memoirs of a Geisha” come to mind.

Zaghmout’s book is not a literary novel like theirs; in fact, it verges on melodrama, but it is a story that needs to be told, a novel that obviously emerges from strong motivation to catalyse social change. Having originally written “The Bride of Amman” in Arabic testifies that his aim is to generate discussion, not simply to expose.

Transgressing taboos opens the characters up to new sides of their personalities and more positive ways of relating to others. “Are our ideas like clothes?” Leila queries. “They seem to fit initially, but they become too small for us as our awareness about our surroundings grows, and then it’s perhaps time to throw them off and replace them with new ways of thinking.” (p. 227)

While Zaghmout declares war on outdated social norms that complicate and sometimes destroy people’s lives, he does not declare war on society as such. The story points to a number of avenues for reconciliation if only people are open-minded and respectful of others’ individuality and dreams. “The Bride of Amman” is a brave intervention in a debate that is going on just below the radar. Let’s bring it out in the open, he seems to be saying.

Related Articles

10 Minutes 38 Seconds in This Strange WorldElif ShafakLondon: Viking/Penguin Random House: 2019Pp.