You are here

Where local and global intersect

By Sally Bland - Oct 26,2014 - Last updated at Oct 26,2014

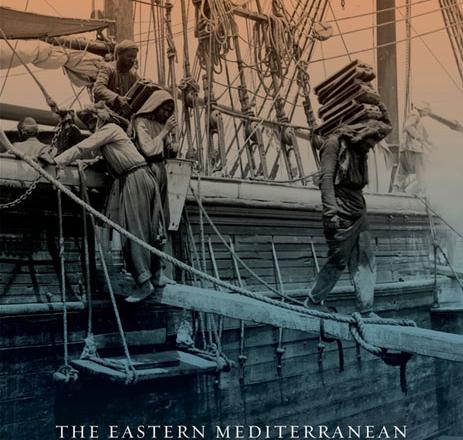

The Eastern Mediterranean and the Making of Global Radicalism, 1860-1914

Ilham Khuri-Makdisi

Berkeley: University

of California Press, 2013

Pp. 279

In the past few decades, the term globalisation has been used to refer to the relative eclipse of borders by multinational conglomerates and communication systems, such as the Internet. This book, however, returns to an earlier stage of globalisation that coalesced in the late 18th and early 19th century. In the introduction, historian Khuri-Makdisi states her intention to “normalise the history of the Eastern Mediterranean and move away from exceptionalist narratives regarding the Arab world, the Ottoman world, and Islam.” (p. 9)

She does so by examining the Eastern Mediterranean’s strong global linkages over a century ago, and the related spread of radical ideas in the region comparable to what was happening in many other parts of the world. The book focuses on Alexandria, Cairo and Beirut — all hubs of economic and cultural exchange at that time. An important, and often forgotten, part of this exchange were radical leftist ideas derived from socialism and anarchism, and espousing the causes of social justice, workers’ rights, mass education and anti-clericalism.

In Khuri-Makdisi’s view, the spread of radicalism was connected to the “tremendous changes” occurring in the cities of the Eastern Mediterranean, especially Beirut, Cairo, and Alexandria, at the time: “Their populations swelled, their geographic areas doubled or trebled… The cities were further incorporated into the world economy and became plugged into global information and communications networks, which allowed news from all over the world to reach them promptly, thanks to the telegraph, news agencies, a reliable postal system, and a plethora of periodicals.” (p. 3)

Moreover, colonial domination was looming, as seen in the 1882 British occupation of Egypt, and land issues were becoming acute. The mass dispossession of peasants in Mount Lebanon, like in Italy and elsewhere, led to massive emigration to the Americas. There was also extensive migration within the Eastern Mediterranean itself, bringing Syrian intellectuals, Italian anarchists as well as workers from Italy, Greece, Malta, Syria and elsewhere to the urban port cities, and Egypt in particular. At the same time, economic changes and modern education contributed to the rise of the middle class, and brought to the fore an intellectual strata that gained prominence in the “nahda” or Arab renaissance.

In successive chapters on the press, the theatre, radical political networks and labour unrest, the book documents the people, publications, cultural events, institutions and labour activism that introduced radical new ways of looking at the world, and acting to change it. New periodicals kept the reading public informed of world events and discussions, pointed out parallels to the local situation, and connected people and ideas throughout the region and beyond, including Arab communities as far afield as Brazil. Yet it was theatre that served as the primary site connecting intellectuals with the public at large. Reportedly, the prominent Muslim intellectual and reformer, Jamal Al Din Al Afghani, “viewed the establishment of an Egyptian theatre as the most effective way of promoting radical ideas and raising the political consciousness of the populace”. (p. 67)

Khuri-Makdisi’s in-depth research points to previously hidden or ignored aspects of the social movements of this period. For example, the nahda is usually discussed as a precursor to Arab nationalism, and many historical accounts omit mention of socialist or leftist ideas in the region prior to the World War I. In contrast, Khuri-Makdisi, without belittling its nationalist aspect, understands the nahda as part of “a global and increasingly radical phenomenon… Contrary to a widely held belief, I argue that socialist and radical ideas were alive, often discussed and incorporated into the nahda, rather than being ‘inconsequential’ topics confined to the work of a few lone individuals,” as some historians have contended. (p. 35-36)

In a rapidly changing environment, the activities of radical intellectuals in the Eastern Mediterranean made them “full participants in the making of a globalised world, albeit perhaps offering an alternative vision of this world or even challenging and subverting the version created and maintained by European imperialism”. (p. 2)

This book is well-written, carefully documented and includes myriads of fascinating details to bolster its main arguments. Khuri-Makdisi argues persuasively for a fresh, more comprehensive reading of this seldom-studied snatch of history which she brings to light. “The Eastern Mediterranean and the Making of Global Radicalism, 1860-1914” is available at Books@Cafe.

Related Articles

Winds of Change: The Challenge of Modernity in the Middle East and North AfricaEdited by Cyrus Rohani and Behrooz SabetLondon: Saqi Books, 2

Fragile Nation, Shattered Land: The Modern History of SyriaJames A. ReillyBoulder/London: Lynne Reinner Publishers, 2019, Pp.

Shifting Sands: The Unravelling of the Old Order in the Middle EastEdited by Raja Shehadeh and Penny JohnsonUS: Olive Branch Press/Interlink