You are here

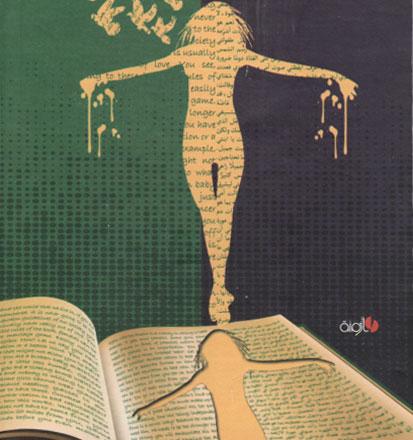

‘Writing truths through fiction’

Apr 22,2018 - Last updated at Apr 22,2018

Inkshedding Gender Politics: Academic Activism in Feminist Theory

Rula Quawas, editor

Amman: Azminah, 2017

Pp. 216

This groundbreaking book grew out of Rula Quawas’s conviction that storytelling and feminism are interconnected: “Writing is a source of power in itself. It is, in essence, an act of being, creating, and existence, and writing truths through fiction is particularly powerful.” (p. 26)

Accordingly, she asked her students in the literature and feminist theory course she taught at Jordan University, to write short stories about how gender norms affect the lives of women (and men) in Jordan, believing that this would help them find their own voices as a step towards making change. Indeed, as she anticipated, in the stories included in this book, the “student-authors attempt to make gender politics… more visible, and to explore possibilities for transforming them”. (p. 15)

“Inkshedding Gender Politics” shows the degree to which students have been inspired by Quawas in her capacity as professor of English and feminist theory, founding director of the Centre for Women’s Studies at Jordan University, friend and mentor. In her inclusive perspective, feminism and literature are not isolated from society. Rather, “the feminist classroom in Jordan creates a culture of polyvalent voices, a culture of democracy and a culture of speech… [drawing] attention to the emergent role of women bargaining over and negotiating their subversion and resistance, as well as their more intangible, cognitive processes of reflection and analysis, pointing to a new consciousness from which deeper political and cultural transformations follow”. (pp. 27-28)

The book also shows how much talent and insight her students possessed, just waiting to be unleashed. However, it almost did not see the light of day due to Rula’s tragic, untimely death. Luckily, Leen Quawas and Hani Barghouti were able to reconstruct the text from Rula’s laptop.

Of the twenty-six stories included in the book, most are in English, the language of the class, and a few are in Arabic. Most are written by local women, but several are written by study-abroad students from the United States. One of the more complex stories is written by a man, showing that feminism is a humanist issue, not confined to women alone. Some are “bruised narratives” in Quawas’s words (p. 33), while others hold out hope that women can gain control of their lives and follow their dreams.

The pitfalls of marriage enter into almost every story — women pressured into marriage too young or because they are presumably getting too old, women married to much older men, to psychologically or physically abusive men, to a cousin rather than someone they love. In some stories, the woman’s parents are indifferent to her suffering; in very few, they support her.

The other prevalent theme is the importance of women getting higher education and dealing with the obstacles erected in their way. Many stories evidence how women face the false dichotomy of getting an education or getting married; some give up and marry, while others insist on their right to an education. Then there is the next obstacle — it is okay to be educated but not to work.

A very touching story is about a young woman who is continuing her education and working in order to support her mother after her father’s death and her brother’s desertion. On top of her overburdened schedule, she must bear the criticism of neighbours who see her coming home late at night after work, but she does not give up, considering education her greatest weapon.

Several stories show the difference in how boys and girls are raised, and the difference in expectations of each. A particularly poignant story about a young woman, who tries to rescue her high school friend from parental abuse, is also an indictment of social institutions’ failure to help victims of domestic violence.

One young woman steels herself to resist the pressure to marry before she is ready by writing about her feelings, and thus confirms the overall theme of the book: “The words hearten her soul, for she is no longer trapped in silence.” (p. 66)

Another young woman finally tells her mother that getting married is not her main goal because she wants to continue her graduate studies. “From that day on, one of the masks Sara wears cracks a little revealing an inch or two of her real skin.” (p. 76)

Two stories feature the negative reactions of a husband or family to the birth of a girl instead of a boy. In one, the woman reacts by naming her daughter Amal (Hope); in the other, the woman persists over the years until her husband finally recognises the value of their daughter.

As they argue against stereotypes of women, the stories do not romanticise women or stereotype all men. In fact, many stories reveal the role of other women in enforcing patriarchal norms.

An interesting story rotates back and forth between the lives of a Jordanian girl and an American one, showing that elements of patriarchy are still entrenched in the US.

All in all, the stories live up to the dedication of the book: “For all young women who dare to step out of the history that is holding them back and into the new story that they are willing to create.” (p. 5)

Sally Bland

Related Articles

AMMAN — Celebrating the voices of Jordanian women who “are not afraid to break the silence”, and as a testament of proud and brave voices, 1

Bad Girls of the Arab WorldEdited by Nadia Yaqub and Rula QuawasAustin: University of Texas Press, 2017Pp.

AMMAN — Stereotypes about the roles of women in society hinder their economic and political participation, experts said, calling for an educ