You are here

Delving into Ancient Jordan’s necropoleis through funerary portraits

By Saeb Rawashdeh - Apr 08,2024 - Last updated at Apr 08,2024

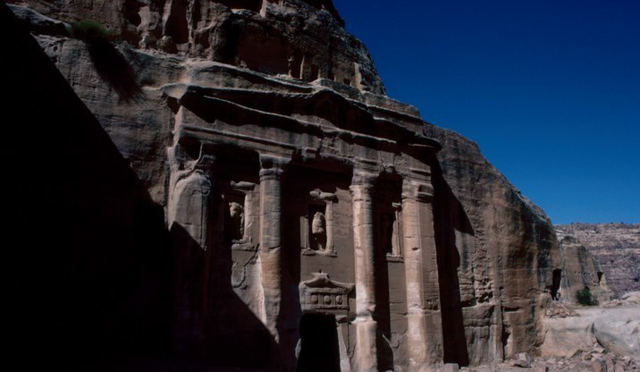

The Tomb of the Roman soldier in Petra (Photo courtesy of ACOR)

AMMAN — A funerary portrait serves as the lasting image through which the deceased hoped to be remembered by posterity for all eternity. It was a very important artistic and archaeological evidence about the urban life in the Hellenistic and Roman Near East, from the province of Arabia or from the Decapolis. Stelai, busts, sarcophagi, statues, tomb façades, doors and painted frescoes tend to depict social values of the patrons and family of the deceased. These objects of art are very often correlated with religious customs and practices.

The Roman Jordan was no exception compared to the rest of the Near East during the Roman rule, as funerary portraits were displayed on a different media.

“The choice of the commemorative monument and particularly that of the portrait, was evidently determined by a combination of factors, such as the patron’s personal taste and financial means, the varying access to material [marble, limestone, basalt, sandstone, etc.] and talent [sculptors and painters, and their more or less specialised workshops], as well as the architectural setting into which the funerary artefact was integrated,” noted Bilal Annan from The University of Groningen, adding that different factors coalesced to produce a miscellaneous archaeological record of funerary portraiture in Jordan, since one encounters these images on tomb façades, sarcophagi, frescoes, and in the form of busts and even statues.

Naturally, some tombs would have exhibited a combination of these artistic forms, which may illustrate the breadth of the typological and iconographic spectrum available for patrons to choose from, Annan continued, adding that no evidence of funerary portraits that can be unquestionably dated to the Hellenistic period seems to have survived in the North Arabian realm, which is not to say that Hellenistic tombs in Jordan were devoid of sculptural ornaments: excavations conducted in the necropoleis of Gadara (Umm Qais) and its surroundings have brough to light statues of sphinxes, lions, and other feline creatures which were meant to protect the tomb from violation and desecration.

According to Annan, the oldest protected funerary portraits are preserved in Petra, in a form of rock-cut façade. Some of them have eroded or their images were defaced or completely destroyed. They range from 1st century BC until the late 1st century AD.

“The Obelisk Tomb, where a draped figure is carved in a naiskos amid four monumental obelisks; the Urn Tomb where a slab bears the image of the owner of the tomb, perhaps a king; the Silk Tomb on the façade of which are carved two heavily eroded reliefs, which may be interpreted as the Dioscuri—owing to the apparently mounted horseman on the left, and the eroded horse figure inserted between the male figure and the edge of the frame to the right —or alternatively, as officers of the Nabataean cavalry; the so-called ‘Turkmaniyyeh’ Tomb, where two busts are set in a rather small niche above a long Nabataean epitaph; the misnamed ‘Tomb of the Roman Soldier’; and Tomb of Arrianos,”Annan elaborated.

Outside Petra, surviving funerary portraits carved on tomb façades are rare: “The first was recorded in Abila Quwayliba, where a bust, adorning the entrance of the aptly named ‘Tombeau aux bustes’ is shown under a sort of rudimentary pediment, flanked by small-scaled figures set in small niches, with their hands placed on their hips. The second relief, which has been somewhat overlooked in recent literature, can be admired on the façade of the Western tomb in the ‘Al-Kahf ‘ funerary complex outside Amman, where a defaced bust, draped in a mantle and possibly holding a scroll in one hand, is carved in the tympanum, amid a dense network of intertwined floral motifs,” Annan elaborated.

According to Annan, the corpus of funerary portraiture that he assembled in Roman Jordan numbers 219 items. Out of this number, 95 hail from Abila and 62 from Gadara and these cities have the biggest number of funerary portraits in Jordan, while the citizens of Gerasa, for instance, seem to have favoured plain sarcophagi decorated with pelta shields.

“Certainly this discrepancy among Decapolitan cities in regards to funerary portraiture cannot be solely ascribed to the varying intensity of archaeological surveys and exploration, but must have reflected a marked preference among the inhabitants of these two cities for funerary self-representation, and one may detect, upon closer inspection, idiosyncratic and polis-specific trends in this art form ,” Annan stressed, adding that the recurrence of a finite number of iconographic schemes and attributes , which can be observed throughout the Graeco-Roman Mediterranean, allows us to appreciate the extent to which the Classical visual language (koinē) permeated Decapolitan aesthetics, and found vivid echoes within Nabataean culture.

Related Articles

AMMAN — A sarcophagus (plural “sarcophagi” or “sarcophaguses”) is a coffin commonly carved in stone and displayed above ground. During

AMMAN — Busts are among the most widespread forms of funerary depictions of a deceased individuals.

Cairo — Egypt on Saturday unveiled an ancient tomb, sarcophagi and funerary artefacts discovered in the Theban necropolis of El Assasif in t