You are here

Jordan Museum: Studying Greek-Roman inscriptions from Levant

By Saeb Rawashdeh - Apr 02,2024 - Last updated at Apr 02,2024

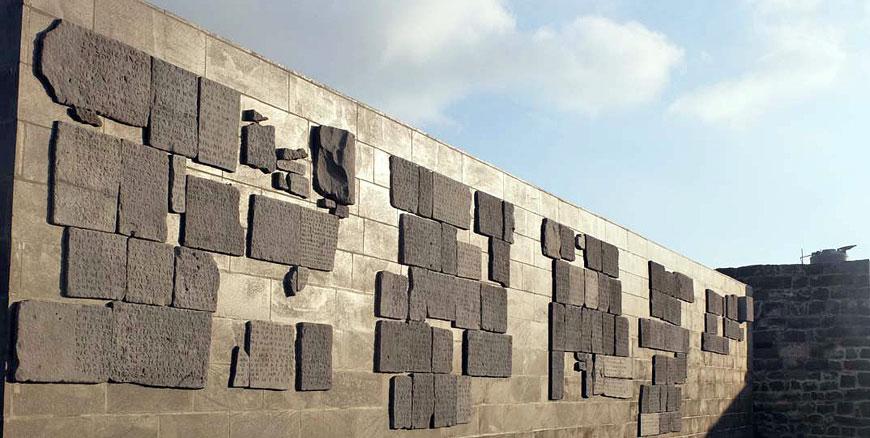

A part of edict of Emperor Anastasius(491 AD-518 AD), the ruler of the Byzantine Empire at Qast Hallabat (Photo courtesy of ACOR)

AMMAN — The Jordan Museum, located in a very busy area of Ras Al Ain, is home to many inscriptions from various parts of the country. The reason why the modern building was erected in the downtown area was to attract both tourists, who roam around that neighbourhood, but also to introduce the Jordanians with their history and cultural heritage.

The collection of Greek inscriptions is displayed at the museum and they are the joint effort of different Jordanian and international scholars who worked under the umbrella of the Department of Antiquity. These inscriptions are just a small segment of the rich Jordanian and Levantine cultural heritage and inscriptions are sorted in geographic order from north to south. Each inscription is followed with a photo, translation and transcription with brief comments on their historical and archaeological context.

One of them is a building inscription from Gadara (modern Umm Qais). It says: “Good Fortune, Aurelius Diophantos, son of Gaianos, being astynomos, made the nymphaeum with the marble statue at his own expense for the fatherland.”

This inscription reminds the reader of the offering of a monumental fountain by a rich magistrate. The building was partially cleared north of the Gadara decumanus near the market basilica, noted a French scholar, Pierre Louis Gatier, from the University of Lyon, whostudied the inscriptions in Jordan and Syria since decades.

“The donator, Aurelius Diophantos, was a Roman citizen. His father, Gaianos, had a common Latinname, derived from the praenomen Gaius. If he was not a Roman citizen himself, he was at least Romanised,”Gatier explained, adding that the nomen Aurelius implies a date in the 3rd century AD (after 212 AD).

Astynomoi were civic officials responsible for the repair and maintenance of buildings and roads.

“They were in charge of tasks such as boundary disputes, waste collection, house-planning or street repairs. There are few other examples in the Near East: three in Bostra and one in Gerasa,”Gatier underlined.

Another Greek inscription is a mosaic dedication from the church in Hosn, near Irbid.

It says: “By divine grace, under the most pious archbishop John, by the zeal of the pious priest and paramonarios Kyriakos, this church was paved with mosaics, on the 1st of the month Artemisios, in the time of the 13th indiction, in the year 430AD.”

John, archbishop of Bostra, is mentioned in ca 539 / 540 AD and the name of the archbishop, the order of the alphanumerical signs and the date according to the computation of the Provincia Arabia fit well together and clearly show that Husn belonged to the territory of Bostra, metropolis of the province. It shows the large size of the territory of Bostra, which extended far to the south and the west.

Elias must have been the donator of the mosaic but his function is not well defined, Gatier interpreted. “If he was strategos, he may have been governor of the province; Both strategos and stratelates translate the Latin title magister militum, which refers to senior military officers,” he continued.

However, for a person of distinction, we would expect a clearer description. A modest dedication at a secondarysite like Al Husn may rather point to another function, that of stratiotes or “soldier”.

From Gerasa(Jerash) came an inscription that says: “Antoninus, son of Antiochos, from Alexandria: he made [this] himself.”

A German scholar, Thomas Weber-Karyotakis, worked with his team in the Eastern Bath compound where this inscription came to see the light. The white marble used for this statue was quarried on the island of Thasos, and the text of another inscription was published in capital letters by Weber-Karyotakis.

“It is a dedication of a statue offered by a Gerasene, Lysias, son of Ariston, to the city of Gerasa, his homeland, in the year 181 or 281 of the Gerasene era [118 / 119 or 218 / 219 AD], Gatier said.

According to Weber-Karyotakis, the first date would fit more accurately with the slight remains of the hundreds digit. Without knowing of the second inscription, and based only on stylistic comparanda of the statue and of the shape of the letters, it is suggested that the statue was sculpted in the late second or early third century AD.

From the early 2nd century comes the following epitaph found in Gerasa:”“Farewell, to you and to the reader, Marcus Ulpius Sophron, imperial freedman, made [this] for Eutyches, his own slave, who was worthy of it and who lived 19 years.”

According to Gatier, Marcus Ulpius Sophron, the master, was one of several imperial freedmen and slaves who held a position in the financial office of Provincia Arabia, under the authority of the equestrian procurator at Gerasa.

“This province is remarkable because the two heads of the Roman administration were located in two different towns: The governor at Bosra and the procurator at Gerasa. When he was a slave, Sophron had a simple Greek name [‘Wise’, ‘Temperate’], very appropriate for his function of clerk. He was certainly freed by the emperorTrajan, whose cognomen and nomen he obtained while becoming a freedman and Roman citizen Eutyches (‘Well-chanced’, ‘Fortunate’],” Gatier elaborated.

The Latin inscription on the funerary altar of a third Eutyches, “freedman of the emperors”, points to the same social milieu of Greek- and Latin-speaking slaves or ex-slaves with strong financial skills who later became administratives.

Related Articles

AMMAN — Greek inscriptions containing more than 300 lines and approximately 70 chapters engraved in 160 basalt blocks have been found in sec

AMMAN — Peaceful relations between the Arab world and Europe go back to the period of antiquities, according to a German professor. Spe

JERASH — After years of meticulous work, a French archaeological team that has been excavating the eastern Roman baths in Jerash, unearthed