You are here

From Fallujah to Maghreb, a new, diffuse Al Qaeda

By Reuters - Jan 16,2014 - Last updated at Jan 16,2014

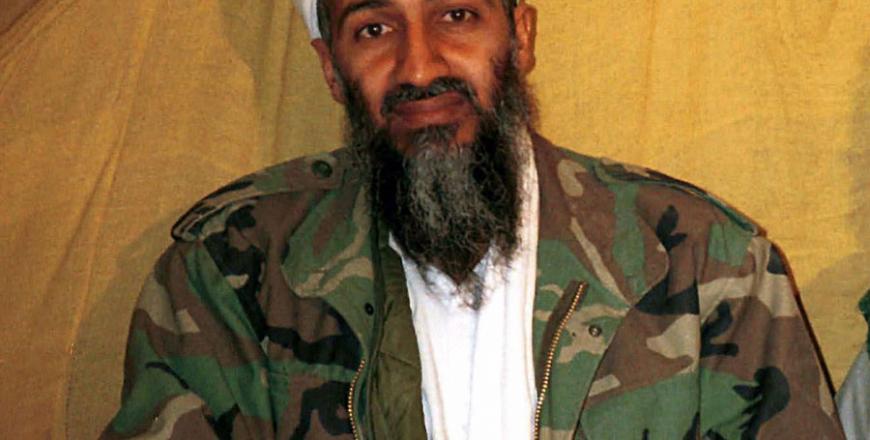

LONDON — More than two years after the death of Osama Bin Laden, the turbulent aftermath of the “Arab Spring” has helped his group — or more accurately, its offshoots and successors — gain ground.

Two weeks ago, fighters from Al Qaeda affiliate the Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) took over much of the central Iraqi city of Fallujah, reversing their defeat at the hands of US forces and local tribal allies almost a decade ago.

Western officials fear associated groups will carve out havens in Libya, Syria, West Africa and perhaps Afghanistan once NATO troops withdraw.

But the new generation is very different to the tight-knit group that planned the September 11, 2001 attacks, security experts and officials say.

Groups such as ISIL, Somalia’s Al Shabaab or Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) have primarily local aims and are much less concerned with the Western “far enemy”.

In a video posted on YouTube on December 17 which Western intelligence agencies have been studying, a man in a balaclava snaps rounds into a Glock handgun magazine and, in a pronounced English Midlands accent, calls on British Muslims to join him in Syria, “the land of jihad”.

But the unidentified man does not mention attacking the West once. Instead, his ire is directed at the forces of Syrian President Bashar Assad and the western-backed Free Syrian Army.

Heightened strains over the Syria war between Shiite Muslim Iran and Sunni power Saudi Arabia, who back opposite sides in the conflict, are contributing to sectarian tensions around the region and encouraging Gulf Arab sympathisers to increase funding of aggressively Sunni Al Qaeda affiliates.

But there is little sign of common purpose.

“There are probably more people fighting now under the Al Qaeda banner than ever before,” says Richard Barrett, head of the United Nations Al Qaeda and Taliban monitoring team until last year and now at the Soufan Group Consultancy. “But that doesn’t mean they are necessarily fighting for the same thing or even on the same side.”

Even as it raised its flag in Fallujah this month, ISIL was being evicted from its headquarters in Syria’s second city of Aleppo by Islamist groups including the Al Nusra Front, a rival Al Qaeda affiliate.

Letters captured from Bin Laden’s compound in 2011 show him struggling to control Al Qaeda’s affiliates and worrying that Al Qaeda in Iraq — now ISIL — was killing too many civilians and alienating Muslim opinion.

His successor, Ayman Al Zawahiri, opened Al Qaeda further to include groups such as Al Shabaab and now faces similar problems. In a letter last year, he called for ISIL to leave Syria to Al Nusra, a request it ignored.

“Most of those now claiming to be Al Qaeda would never have even been allowed into the (pre-September 11) movement,” said Nelly Lahoud, a senior researcher at the US Military Academy Combating Terrorism Centre who examined Bin Laden’s documents.

Still, Western spy chiefs have worries. Officials say hundreds of British and other European Muslims — as well as a smaller number of Americans — are fighting in Syria alone and will have to be monitored on their return.

“We are having to deal with Al Qaeda emerging and multiplying in a whole new range of countries,” John Sawers, head of Britain’s Secret Intelligence Service (MI6), told a parliamentary panel in November. “There is no doubt at all that the threat is rising.”

The greatest Islamist militant risk to targets in the West, most officials and experts say, now comes from small-scale attacks with guns, bombs or knives along the lines of last year’s April 15 Boston bombing and May 22 killing of a British soldier in Woolwich, London.

Britain’s MI5 says well over half of the 34 plots it foiled between the July 7, 2005, London bombings and the Woolwich attack involved those already in the country. In most cases, however, there was also some tangential link to a foreign jihadi group.

Michael Adebolajo, one of two British Nigerian men who killed soldier Lee Rigby, had been arrested in Kenya in 2010 on suspicion of travelling to train with Al Shabaab in Somalia.

In its links to “AQ Central” and enthusiasm for attacking the West, Al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) is seen as perhaps the closest to the old Al Qaeda model — although much of its focus remains on its local fights in Yemen and Saudi Arabia.

AQAP in particular has put considerable energy into reaching out through websites and forums.

Boston bomber Dzhokhar Tsarnaev told investigators he learnt to build the pressure cooker devices that killed three and injured 264 from an AQAP online magazine.

Overstating or understating?

Even within intelligence circles, there is growing disagreement over the nature of the threat.

“Everyone is asking themselves the same question: is it still meaningful to talk about Al Qaeda as a single organisation and if not, what are we dealing with?” says Nigel Inkster, former MI6 deputy chief and now head of transnational threats at the International Institute for Strategic Studies.

US logistic support and intelligence — sometimes including drone strikes — has proved relatively effective in pushing back AQAP in Yemen and Al Shabaab in Somalia. In Mali, Washington worked with French and regional forces to force AQIM out of swathes of the country.

Denying such groups territory, however, only goes so far. US officials believe AQIM’s numbers remain largely undiminished.

There is also increasing opposition to such US-led action. Syria’s Assad seems unlikely to allow drones to operate in his country, while both Pakistan and Libya appear increasingly opposed to unilateral US action.

Nor are Washington and Baghdad likely to dramatically step up military cooperation, although drones have been sent.

Some suggest the Al Qaeda label may be distracting foreign powers from the reality of what are often local conflicts. What happened in Fallujah, they say, was as much about frustration amongst local Sunni tribes with the majority Shiite government.

Others, however, fear complacency.

“Many want to trumpet the demise of core Al Qaeda and take solace in the belief... that what we are seeing in Africa and the Levant is not part of some grand strategy,” says Georgetown professor and sometime US official Bruce Hoffman, one of Washington’s leading experts on the group. “Wishful thinking.”

Related Articles

Osama Bin Laden was fixated on attacking US targets and pressured Al Qaeda groups to heal local rivalries and focus on that cause, according to documents the United States says were seized in Bin Laden’s hideout in Pakistan and released on Wednesday.

Al Qaeda in Yemen Wednesday claimed responsibility for the deadly attack on Charlie Hebdo, saying it was ordered by the jihadist network's global chief to avenge the French magazine's cartoons of the Prophet Mohammed.

WASHINGTON — US President Donald Trump on Saturday confirmed that Hamza Bin Laden, the son and designated heir of Al Qaeda founder Osama Bin