You are here

With Libya’s transition paralysed, a would-be premier projects power in Tripoli

By Reuters - Mar 02,2017 - Last updated at Mar 02,2017

Libyans take part in celebrations marking the sixth anniversary of the Libyan revolution in Tripoli, Libya, February 17, 2017 (Reuters photo)

TRIPOLI — In a cluster of luxury residences that survived Tripoli’s battles almost unscathed, a self-declared defender of Libya’s revolution has set up base as one of three claimants to the country’s premiership.

A handful of guards and two armoured white SUVs are stationed at Khalifa Ghwell’s compound, and loyalists control surrounding roads with checkpoints and patrols.

Few consider Ghwell a serious contender for power. But in recent weeks the ex-prime minister has bolstered his presence at his base 4km from the heart of the capital, in an increasingly brazen challenge aimed at undermining a UN-backed government that was meant to shepherd Libya towards peace.

Six years after the NATO-backed uprising that toppled Muammar Qadhafi’s over 40-year rule, Ghwell’s reappearance and his ability to mobilise powerful armed support have set the capital on edge, leading to some unusually violent fighting.

They expose Libya’s deep fractures and how little traction Western efforts have gained in stabilising the oil-producing desert state.

Libya remains a byword for chaos. The North African country has more than doubled oil output to 700,000 barrels per day in recent months, though this is well below the more than 1.6 million bpd it pumped before Libya’s 2011 uprising.

That recovery and gains against the Daesh terror group are fragile. The south and west are criss-crossed with smuggler routes, and armed brigades skirmish in turf wars on the streets of Tripoli.

In the capital, Prime Minister Fayez Sarraj’s UN-endorsed Government of National Accord (GNA) has drifted half-formed, largely unable to provide services to despairing citizens or exert authority even on its doorstep, as Libya’s neighbours and Western states scramble to salvage their plan.

In the east of the country another premier also lays claim to power from the city of Bayda, backed by a parliament that sits in Tobruk, near the border with Egypt. It won international recognition but is now largely inactive.

They are aligned to an anti-Islamist figurehead, Khalifa Haftar, who is based in the town of Marj and whose forces have long been fighting for control of the nearby city of Benghazi. Haftar has been nominating military governors and threatening to move on Tripoli, emboldened by support from Egypt, the United Arab Emirates and Russia.

Haftar’s forces control most of Libya’s oil, and cooperate with the Tripoli-based National Oil Corporation despite earlier attempts by eastern factions to sell oil independently.

Fractured landscape

Divisions that flared into conflict across Libya in 2014 have not healed. Ghwell himself was installed by an Islamist-leaning alliance of former rebels that won control of Tripoli that year from groups aligned with Haftar. Their alliance then fractured, complicating an already messy political landscape.

Since the GNA stalled, Ghwell has been trying to rebuild his position with support from his home city of Misrata.

“What has this government achieved during this year?” Ghwell asked during a rare interview with Reuters, speaking in a wood-panelled office in a complex built by Qadhafi for favoured functionaries.

“Unfortunately the international community sees the results of their support. We thank them for their work but the result is very negative. If they persist with this, nothing will change.”

In an example of the bewildering nature of the country’s post-revolt politics, he says he is now in contact with the eastern-based government aligned with Haftar, trying to strike a deal over the heads of the GNA that they both oppose.

But he says if Haftar tried to seize power in the capital, he would be outgunned. “We are ready for this,” Ghwell said.

A year ago, Ghwell tried and failed to prevent the GNA leadership from even getting to Tripoli. He shut down the air space over Tripoli, but was outmanoeuvred when Sarraj travelled from Tunisia by ship in late March, landing at a naval base that is still his headquarters.

Ghwell accuses the GNA of trying to impose itself without popular backing, creating further layers of institutional confusion and overseeing a steady decline in living standards.

His entourage moved into the residential complex, and a parliament building where a pro-GNA body had been sitting, in October. In January, he announced he had taken back a number of ministries. He says he now has authority over “about six”, including defence, justice and “50 per cent of the interior ministry” — a claim the GNA dismisses. They say Ghwell makes fleeting appearances at unoccupied official buildings.

Limits to government

But the limits of GNA control are clear. Its nine leaders, or Presidential Council (PC), were meant to unite Libya’s political currents and its regions, east, west and south, but have often amplified those splits.

Two members with ties to Haftar and his allies have almost entirely boycotted the council, and others have frequently clashed, issuing contradictory statements and making apparently unilateral appointments, often announced late at night.

Sarraj’s frequent absences at international meetings and summits have fuelled criticism that his government is dependent on foreign support and barely visible on the ground.

Western powers eagerly promoted the GNA as a partner, and the PC gradually tried to put its ministers to work. But without the endorsement of the eastern parliament — a key step in the UN-backed political accord — they are left in limbo.

Sarraj has claimed credit for victory over Daesh in its former stronghold of Sirte and for boosting oil production, but both were driven by forces largely outside his control.

The international community has coaxed a reluctant central bank to release funding to the GNA, which has in turn struggled to operate. Few resources trickle down, even to ministers.

Iman Ben Younis, a minister in charge of building and reforming state institutions, has just three employees, all of them volunteers at her office in the prime ministerial building.

‘Losing faith’

Otman Gajiji, who resigned as head of Libya’s municipal elections committee because his staff had not been paid for two years, said mayors who backed the GNA were fed up.

“They’re losing faith, some of them have informed me that they will withdraw their support,” he said.

Ahmed Maiteeg, a deputy prime minister, says the PC has some spending power after the central bank recently releasing budget money. He said he was untroubled by Ghwell, whose instructions “don’t go further than his secretary”.

Maiteeg said the GNA’s role was to “maintain the peace” between Libyans, and brigades of former rebels that divide up the capital — some with semi-official status — will be given economic opportunities and return to civilian life.

But engaging armed groups is not easy. Militiamen kidnap civilians for ransom, force banks to hand over cash, and steal electricity to save their neighbourhoods from power cuts.

In recent battles armed groups have coalesced into pro- and anti-GNA factions, the latter spurred on in weekly addresses by Libya’s grand mufti, an influential figure for some brigades.

The anti-GNA side was recently reinforced by a convoy of military vehicles that arrived in the capital from Misrata, sparking fresh clashes. Last week they were blamed for firing on Sarraj’s motorcade as it passed close to Ghwell’s compound.

Related Articles

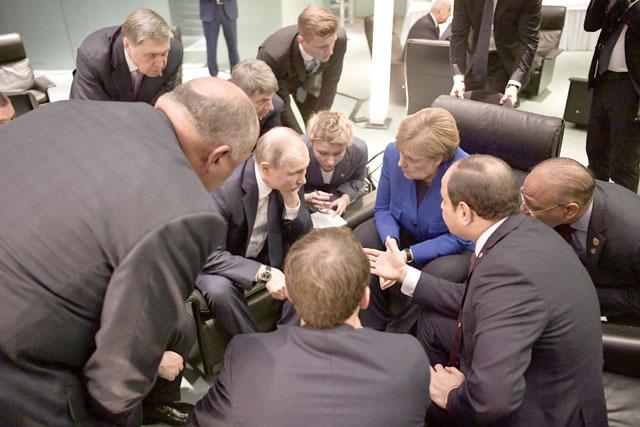

BERLIN — World leaders committed on Sunday to ending all foreign meddling in Libya's war and to uphold a weapons embargo at a Berlin summit,

TRIPOLI — Libya’s military strongman Khalifa Haftar launched an offensive three months ago to seize the capital, the seat of the internation

MOSCOW — Russia's foreign minister on Thursday pushed an "inclusive national dialogue" in Libya at talks with its UN-backed premier that cam