You are here

Scientists find possible link between Zika and birth defect

By The Baltimore Sun (TNS) - Mar 06,2016 - Last updated at Mar 06,2016

Photo courtesy of elcomercio.pe

BALTIMORE — When scientists in Brazil suspected a link between a troubling upswing in a birth defect called microcephaly and the mosquito-borne Zika virus last fall, the hunt began for proof. Johns Hopkins neuroscientists and their partners in Florida and Atlanta now say they’ve discovered a big clue.

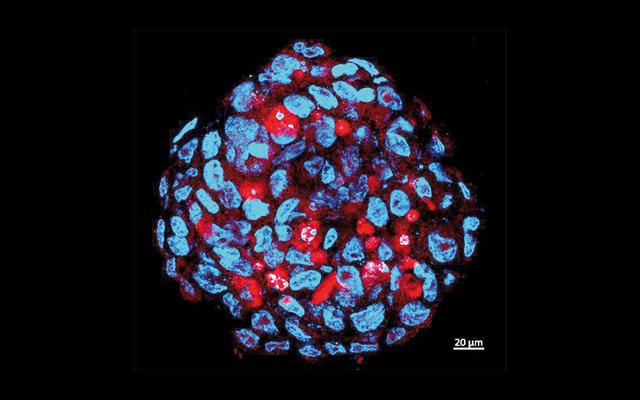

In lab dishes full of stem cells, they may have seen how the virus becomes the disease as cells that are the building blocks of brain development were destroyed or damaged by Zika.

“It was in a dish, not in a foetus,” said Hongjun Song, director of the Hopkins Stem Cell Biology Programme and one of the researchers. “But it fits.”

Proving the link between Zika and microcephaly is important because it would rule out other potential causes for the surge in babies being born with the often deadly birth defect and justify the massive public health response and spending on developing a vaccine.

The Hopkins stem cell study, published Friday in the journal Cell Stem Cell, was accelerated after the World Health Organisation declared a public health emergency on February 1. Zika infections are spreading rapidly throughout Latin America and the Caribbean and more babies were being born in those areas with small brains and heads.

There have been more than 100 cases of Zika in the United States among travellers.

Among those infections were nine pregnant women, four of whom either reported miscarriages and abortions after images showed abnormalities, and one who delivered a baby with microcephaly, according to public health officials. They believe mosquitoes will transmit the virus directly to Americans when warmer weather arrives, particularly along the Southern border where the carrier Aedes mosquitoes are more prevalent.

For the study, two labs at Hopkins produced the specialised stem cells that could grow into brain tissue. The cells were sent to a lab at Florida State University that infected them with Zika. Then they were sent on to a lab at Emory University for analysis.

The team now plans to replicate the effort in a so-called 3-D cell system that will more closely mimic brain development. This could finger Zika more definitively as the culprit for microcephaly or one of them. Other viruses are known to cause the abnormality, and genetic and environmental factors haven’t been ruled out.

But Zika remains the prime suspect, said Dr Anthony S. Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease, which helped fund the study. He said other investigations are under way, including an ongoing study of pregnant women.

“It does not provide definitive smoking gun proof that Zika is the cause of microcephaly,” Fauci said of the study. “But it’s another bit of information among the rapidly accumulating evidence.”

Fauci and leading microcephaly researchers who have seen brain tissue or images of foetuses from Brazil say the cell study results mirror what they’ve witnessed.

Brain tissue of stillborn babies with microcephaly showed nerve cell death and damage, which is what the study showed, adding to the “pool of evidence”, said Dr Ernesto Marques, a University of Pittsburgh microbiologist who is collaborating with Brazilian researchers.

Another study published Friday in the New England Journal of Medicine found evidence that Zika can cause a range of abnormalities in pregnant women, including ones not connected previously to the virus.

Researchers from the University of California, Los Angeles and the Fiocruz Institute in Brazil followed 42 pregnant women who tested positive for Zika and found through ultrasounds and exams that 12 of the foetuses were subject to “grave outcomes”, including foetal death, low to no amniotic fluid, foetal growth restriction and central nervous system damage including blindness. The impacts were seen at various stages of pregnancy and some affected the foetus and others the placenta, which is the foetal life-support system.

The Hopkins team, lead by Song and Dr Guo-li Ming, his wife and fellow neuroscientist in the Institute for Cell Engineering, were using cells derived from human skin to decode other brain disorders such as epilepsy and Huntington’s disease when their students suggested they investigate Zika.

They were about to call Hengli Tang, a virologist friend from graduate school who had a lab at Florida State, to ask if he had a sample of the Zika virus when he rang first. They immediately prepared different cells, including so-called pluripotent stem cells that are made by reprogramming mature cells so they can become any type of cell in the body. One type of those cells, cortical neural progenitor cells, then develop into the nerve cells that make up the cortex or outer layer of the brain.

They sent the cells and a pair of experienced graduate students to Florida and then to Emory to assist in the research. The team found a link in the neural progenitor cells. Three days after exposure to Zika, 90 per cent of those cells were infected and churning out new copies of the virus.

The cells died or failed to divide normally, which in a foetus would stall brain development — the hallmark of microcephaly. The most severe cases, now seen thousands of times in Brazil, showed extremely small brains and heads leading to death or serious disability.

“It’s very telling that the cells that form the cortex are potentially susceptible to the virus, and their growth could be disrupted by the virus,” said Ming, a professor of neurology and neuroscience.

One doctor involved in analysing the foetuses with microcephaly, said the study’s findings “are almost predictable”.

Dr William B. Dobyns, a paediatric neurologist at Seattle Children’s Research Institute, said he saw 15 brain scans of Brazilian foetuses with the same devastating version of microcephaly in recent months. He’d only seen the same pattern two or three times before out of about 6,000 cases of microcephaly he’d reviewed over 25-30 years.

The cases linked to Zika had four things in common: They were all severe and had excess space in the skull as if the brain shrank, malformation of the developing cortex and scarring in the brain. All of that can be explained by the cell study showing cell death and damage, he said.

“It fits like a glove with what I’m seeing on children’s brain scans,” Dobyns said. “The connection between the Zika epidemic and microcephaly is beginning to look very, very real.”

If further study backs up these findings, he said it still may be tough to develop an agent to block the chain reaction into microcephaly. Zika in adults lasts less than a week, and damage likely would be done to a foetus before a women even knew she was infected. It may be more effective to develop a vaccine, he said.

Fauci said several vaccines are in development and some initial testing on humans may be done this year or next, but larger scale trials will take longer and could be stymied if the latest outbreak abates and limits test subjects.

Dobyns said Zika has been around for decades but the link to microcephaly was never made. Either the outbreaks weren’t big enough or public health infrastructure in the affected countries wasn’t sufficient to recognise and report it. Also in past outbreaks in Africa, he said people may have had Zika infections earlier in their lives and developed protective antibodies.

Researchers will continue to investigate the effects of Zika, which also increasingly appears to include another severe neurological disorder called Guillain-Barre syndrome that can lead to paralysis.

In the meantime, officials recommend that women who are pregnant or plan to become pregnant follow the advice of the US Centres for Disease Control (CDC) and Prevention. That includes a warning to avoid travel to more than three-dozen countries with active transmission of the virus and the 2016 Summer Olympics in Rio.

Pregnant women and their partners should “take any recommendation from the CDC very seriously,” Dobyns said.

Related Articles

NEW YORK/BRASILIA — Experts on microcephaly, the birth defect that has sparked alarm in the current Zika virus outbreak, say they are struck

KUALA LUMPUR — Malaysia is bracing for more Zika cases, officials said on Sunday, after detecting the first locally infected patient, which

ORLANDO, Florida — Dr Kenneth Alexander was driving home one day last year when he thought of the idea: What if the Zika virus could be used