You are here

Early Ottoman period neglected by historians — scholar

By Saeb Rawashdeh - Sep 01,2016 - Last updated at Sep 10,2016

Gul Sen

AMMAN — Little attention has been paid to the early Ottoman era, but an abundant collection of documents and records could shed light on the period, says scholar Gul Sen.

Sen, from Germany’s University of Bonn, said that Ottoman rule over Jordan is an understudied phase of regional history, particularly its early years.

“Two periods need to be distinguished: the early and middle periods from 1517 onwards, and the late period, starting with the Tanzimat reform era (1839-1876),” the historian told The Jordan Times in a recent interview.

Although they are quite different, the historian said, only the latter has received sustained attention.

But, over 400 years — the longest period of Muslim rule — a “plethora of archival material” was accumulated, which could shed light on Ottoman rule, as well as the Mamluk period that preceded it, said Sen.

As Mamluk imperial centres came under Ottoman rule, the lands of what would become Jordan were relegated to peripheral administrative status, the professor noted.

Ajloun was subdivided into nahiye (sub-regions) like Karak, Shobak and Salt, she explained, noting that the administrative division of the region changed several times.

The Ottoman empire, which stretched over three continents, was managed by “an elaborate bureaucracy as well as a flexible administration of the newly acquired territories”, she continued.

According to Sen, research has shown that in cities in Jordan, local rulers, clans and tribes were “major players” and could shape Ottoman policy in the periphery.

Original, multi-level research needs to be undertaken, she said.

“For example, at the prominent international conference on the history and archaeology of Jordan held in Amman, in May, only three papers out of more than 200 dealt with the Ottoman period,” Sen stressed.

Regarding the transition between Mamluk and Ottoman rule in the Levant, the scholar said that initially Ottomans “left in place many Mamluk structures, and even political personnel”.

“We know that Sultan Selim I appointed Janbirdi Al Ghazali, the former Mamluk viceroy, as the governor of the larger Damascus province. Only after his 1522 anti-Ottoman rebellion was he replaced by a governor sent from Istanbul,” she noted.

Dynastic periodisation — the categorisation of the past into discrete periods of time based on the ruling dynasty —- plays a very important role for historians when they study a certain region, “especially the pre-modern period”, according to Sen.

The historian is interested in the periods of transition between these dynastically defined political regimes, and co-edited an upcoming book on the transition between Mamluk and Ottoman rule.

“The Mamluk-Ottoman Transition: Continuity and Change in Egypt and Bilad Al Sham in the Sixteenth Century” will soon be published by Bonn University Press.

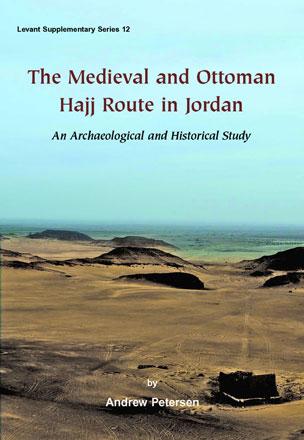

When the Ottomans came to power, one of the first measures they undertook was the building or restoration of caravanserais for Hajj pilgrims, a well-studied aspect of the transition, according to Sen.

The mühimmedefters (registers of important matters of state) contain many orders concerning the protection of the greater Muslim pilgrimage’s routes to Mecca and the functioning of the caravanserais, added the scholar.

The safety of the Hajj route was of crucial importance: “The Ottomans aimed to re-route traffic and provide more secure Hajj routes for the pilgrims from central Asia than those that the Mughal empire (1526-1857) in India could provide.”

“However, this security depended on permanent negotiations between local elements [mostly Arab tribes] and the Ottoman government,” Sen highlighted.

Earlier this year, Sen took part in the Tal Hisban excavation in Madaba, and she later returned to the Kingdom to conduct research at the University of Jordan’s Centre for Documentation and Manuscripts.

She had the opportunity to collaborate with Jordanian experts, and says Professor Muhammad Adnan Bakhit’s expertise was especially helpful.

”Meeting Professor Bakhit was important for me. He is an internationally renowned historian for the Ottoman period in Southern Bilad Al Sham [the Levant],” she highlighted.

Bakhit has enabled the new generation of Jordanian students to read Ottoman texts, so they will be able to contribute to the history of their country in the future, Sen said.

“There is such an abundance of Ottoman documents and records that should be made accessible, but due to the linguistic divide have not been exhaustively used,” the scholar stressed.

“As micro-history offers a different view of things, I will attempt to combine the imperial with the micro-level perspective, that is, to combine the work of historians and archaeologists. Jordan is an exemplar of this collaborative effort.”

Related Articles

AMMAN — The transition between two different periods is characterised by varied and complex factors, as was the case with the transition fro

AMMAN — Despite the abundance of historical resources, the research on caravanserais in Jordan has been overlooked by scientists, according

AMMAN — After the Ottoman conquests in 1517, Syria and Egypt were relegated to a peripheral administrative status by the new rulers, accordi