You are here

Roman treasures of Al Qunayyah: Shedding light on Levantine burial traditions

By Saeb Rawashdeh - Jan 23,2024 - Last updated at Jan 23,2024

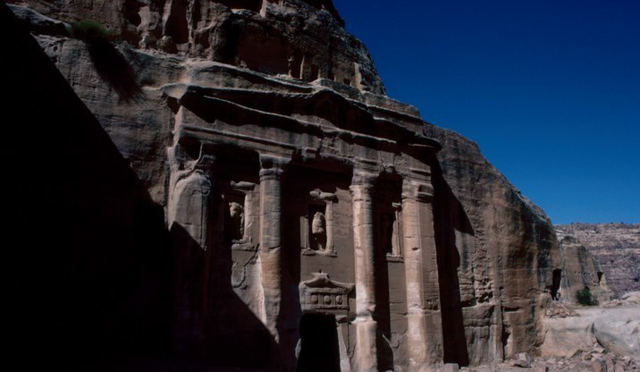

Inscribed votive altar from Al Qunayyah, now in the garden of Qasr Shabib, Zarqa (Photo courtesy of Julien Aliquot)

Al Qunayyah is a site located approximately 10 km southeast of Jerash, and its ancient name is still unknown. Up to the present day, geological and climatic conditions have allowed relatively prosperous agriculture through irrigation, which explains the modern name of the village (from Arabic “small canals”), noted Romel Gharib director of the Department of Antiquities in Zarqa.

“Along the banks of Wadi Qunayyah, dissolution of the limestone has formed karst caves that were used as dwellings, cellars and tombs in antiquity,” Gharib explained, adding that a number of ancient buildings and their foundation layers are visible on the eroded ground surface.

In 2007, two Roman stone monuments were found in the village within a kilometre of each other and they represented different types of porous limestones of local origin.

“They are both of great interest for the history of the site: one of them is a funerary stele which displays figural representations of human busts; the other is a votive altar inscribed in Greek that was dedicated by several priests in the late 3rd century AD,” Gharib said, noting that the votive altar was lying in the olive orchard of a private owner, close to the Ottoman mill.

The funerary stele was found 800 metres away, in the neighbourhood of a modern farm. The stele consists of white limestone with yellow stains and is covered in an extensive transparent ochre patina. The porous stone material, which includes a few fossils, seemingly erodes by flaking.

“The upper bust survives only up to the neck; the head, including the pillar framing as well as the entablature and assumed pediment of the naiskos frame, are missing. This damage occurred in antiquity as the patina runs over the breaks,” noted Professor Thomas Weber-Karyotakis, adding that the preserved parts are much worn by erosion rather than through deliberate human made damage.

Frontal busts are common funerary art in Levant, we can find them in the Decapolis cities, but also in the West Bank and Lebanon.

“The common feature of all these busts is that they are carved in the round from locally available stone. Reliefs on steles, sarcophagi and lintels are rare, as are as full sized statues. Very few busts bear personal names incised on the base,” said Weber-Karyotakis, adding that funerary busts in Jordan and Palestine have some regional characteristics.

Moreover, the custom of placing busts in tombs was clearly not practiced at Capitolias (Bayt Ras) and Adraha (Dar‘a), while only a few specimens are known from Gerasa (Jerash) and Philadelphia (Amman).

“An example of an early 2nd-century AD stele, chiseled in basalt relief and showing the deceased soldier as a half-figure, comes from Gadara. As well as these regional groups in the Levantine hinterland, funerary reliefs occur in great numbers and in different local styles in the Hauran, the Palmyra oasis, the cities along the Euphrates, and in south-western and north-eastern Arabia beyond the frontier of the Roman Empire,” Weber-Karyotakis underlined.

According to the German scholar, the origins of this kind of monument may be sought in late republican Roman Italy, where funerary bust galleries were popular amongst freedmen.

This bust testifies to a provincial group of tombstones on the north-western edge of the Jordanian steppe in the second half of the 2nd century AD and it was influenced by artistic tastes of a nearby Decapolis.

Another stone monument from Al Qunayyah is a funerary bust of a bearded man, probably from Umm Qays (ancient Gadara).

“The monument is made of hard, brownish limestone that includes some natural pebbles, sometimes of large size,” said Julien Aliquot, a French historian, adding that on the upper surface of the block therewas a deep oval hole carved into the stone, presumably for the insertion of a cultic object.

The donors were probably priests from a rural sanctuary at Al Qunayyah or in the surrounding area, Aliquot speculated, adding that they probably dedicated the altar on behalf of a married couple.

“The name of the husband Auktos is a Greek transliteration of the Latin cognomen Auctus. By contrast, the name of his wife is Semitic in spite of its Greek aspect,” Aliquot said.The location of Al Qunayyah north of the Zarqa River, closer to Gerasa than to Philadelphia, indicate that the site belonged to the civic territory of Gerasa in the Roman period, Aliquot concluded.

Related Articles

AMMAN — The Jordan Museum, located in a very busy area of Ras Al Ain, is home to many inscriptions from various parts of the country.

AMMAN — A funerary portrait serves as the lasting image through which the deceased hoped to be remembered by posterity for all eternit

AMMAN — Peaceful relations between the Arab world and Europe go back to the period of antiquities, according to a German professor. Spe